Elie Wiesel was born in 1928 in Sighet, Romania. His mother and father, Sara and Shlomo had 4 children of which Elie was the 3rd, and the only boy. His mother encouraged him to study the Torah. His father ran a small grocery store and was frequently sought out by many of the town’s inhabitants for advice. His father influenced Elie through his humanistic behavior. And as Elie put it, his father “forced” him to learn modern Hebrew. The family spoke mostly Yiddish, and also German, Hungarian, and Romanian. Since his childhood Elie was a voracious reader. Rather than playing outside as a boy, he spent most of his time in the schoolroom or in the synagogue. “When I travel, I am always afraid of running out of books. If I had to describe hell, it would be as a place without books.” As a boy he also studied the violin and played chess.

In May of 1944, the entire Jewish community in his hometown of Sighet was deported to Auschwitz where 90% of them were exterminated upon arrival, including Elie’s younger sister, Tzipora, his mother, and his grandmother. Elie was 15. His father was 50. Upon arrival at Auschwitz a prisoner advised them to lie about their ages and state that they were 18 and 40, so they would be put to work.

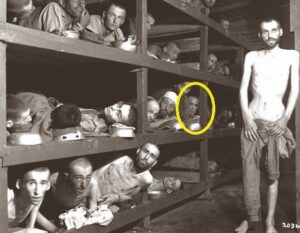

Eventually, Elie and his father were brought to Buchenwald concentration camp. His father died 10 weeks before the liberation by the U.S. 3rd army. Germany surrendered 3 1/2 weeks later on May 7, 1945. Elie was 16.

This photo of Elie in the barracks at Buchenwald was taken just after the liberation. Elie is circled in yellow.

After the war Elie lived in an orphanage in France run by the Children’s Aid Agency. He quickly learned French and in 1947 entered Sorbonne Univ. in Paris, where he studied literature, philosophy, and psychology. Elie attended lectures by the philosophers Martin Buber and Jean-Paul Sartre and studied the writings of Dostoyevsky, Kafka, and Thomas Mann. At age 19 he began working for French and Israeli newspapers as a journalist. He also taught Hebrew, and assembled and conducted a choir.

Elie decided not to speak or write about his experiences in the concentration camps for 10 years. An S.S. officer had said to a young Jew: “Even if you survive, even if you tell, no one will believe you.”

In 1954 Elie interviewed Francois Mauriac, a Nobel Prize recipient in literature, who convinced Elie to begin writing about his experiences.

In 1955 he began writing his account of the Holocaust. It was a 900-page manuscript in Yiddish entitled Un di Velt hot geshveegin And The World Remained Silent. This origignal 900-page version was never published. An abridged version was published in Buenos Aires. He re-wrote it as a shorter version in French entitled La Nuit, published in 1958. And in 1960 the English translation, Night, was published. Eventually it was translated into 30 languages and has sold more than 7 million copies. Wiesel turned down an offer from Orson Welles to make Night into a feature film. He wrote: “The witness has forced himself to testify. For the youth of today, for the children who will be born tomorrow. He does not want his past to become their future. To forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”

In 1956 he moved to New York and worked as a foreign correspondent for an Israeli daily newspaper. His salary was only $175 per month, and there were days when he couldn’t afford food. He soon got a job in the U.N. pressroom.

In 1965 he began traveling to the former Soviet Union to report on the conditions of the 3 million Soviet Jews. They were discriminated against, persecuted and prohibited from practicing their religion. The series of articles he wrote were compiled and published in 1966 in the book The Jews of Silence, about the Soviet Jews and the massacre at Babi Yar in Ukraine. Wiesel called on the American Jewish community to provide support and aid to Russian Jews. This helped to change what had been only a small number of Jews being allowed to leave Russia, to a huge mass exodus. Since the 1970’s over 1.1 million Jews have emigrated out of Russia. Wiesel called his efforts for this cause “a turning point” in his life.

In 1969 he married his Austrian wife, Marion. They had one child in 1972, Shlomo Eleesha, named after Wiesel’s father.

In 1975 Wiesel and the Jewish activist, Leonard Fein, founded the independent magazine, Moment, to provide a voice for American Jews.

Wiesel taught at the City Univ. of New York from 1972-1976 and then at Boston Univ., which created the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies in his honor. He also taught at Yale Univ. and Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Fl. in 1982. From 1997-1999 he taught at Barnard College of Columbia Univ. And he began a 5-year appointment teaching at Chapman Univ. in Orange, CA. in 2010.

In 1979 he wrote the book and play The Trial of God based on his experience of witnessing three Jews in Auschwitz who, close to death, conduct a trial against god, under the accusation that god has been oppressive of the Jewish people.

Wiesel was asked by Pres. Carter to spearhead the construction of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C. He was the Chairman of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council. At Wiesel’s suggestion, the first Day of Remembrance was held on April 24, 1979 in Washington.

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 for speaking out against violence, repression, and racism. In his acceptance speech he explained that silence only encourages the tormentor, stating: “I have tried to keep memory alive, I have tried to fight those who would forget. Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices. The world did know and remained silent. And that is why I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation…Whenever men and women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must–at that moment–become the center of the universe. What all these victims need above all is to know that they are not alone; that we are not forgetting them, that when their voices are stifled we shall lend them ours.”

When he traveled to Oslo to accept the Nobel Prize, he encountered groups of Holocaust deniers, who had gathered in Norway to protest. With the money from the Nobel award, Elie and his wife Marion immediately founded the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity. Its mission is to fight against indifference, intolerance and injustice through international dialogue and youth-focused programs.

He wrote more than 60 books including 2 volumes of memoirs, the 1st: All Rivers Run to the Sea, recounts his life up to 1969, and the 2nd is entitled And The Sea is Never Full, and is about his life between 1969-1999. Wiesel adhered to the same daily work schedule for his entire career. He wrote from 6-10 each morning, working on 2 projects simultaneously, one fiction, and one non-fiction. After writing for 4 hours he then conducted research on the topics he was writing about. He wrote with a photo of his hometown of Sighet in full view. He often wrote 3 drafts of each book, and then cut and edited to achieve a concise result.

He said:

Why do I write?

To help the dead vanquish death.

To forget would be the enemy’s final triumph.

Wiesel is the recipient of the Congressional Gold Medal, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Grand Officer and Grand Cross of the French Legion of Honor, an honorary knighthood from the United Kingdom, and he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was the recipient of more than 100 honorary degrees.

Wiesel advocated for the victims of apartheid in South Africa, the plight of Soviet and Ethiopian Jews, Argentina’s Desapare-cidos, the Kurds, Bosnian victims of genocide in the former Yugoslavia, and he protested against human rights violations in Iran, the Balkans, Rwanda, and Ireland. In the mid-1990’s soon after thousands of Ethiopian Jews were rescued from violence and persecution in Africa, Elie and his wife, Marion, created two educational centers in Israel to provide academic and vocational training to Ethiopian-Jewish children. The centers are a model for other schools. He has championed the causes of Cambodian refugees in Vietnam, and indigenous peoples in Latin and South America including Nicaragua’s Miskito Indians. In his speeches and writings he repeatedly pointed out the existence of so many victims of terror and bloodshed in places such as Rwanda and Chechnya. And he urged Pres. Clinton to intervene in the genocide in Bosnia. In 2003 he discovered and publicized that over 280,000 Romanian and Ukrainian Jews and other groups were massacred in Romanian-run death camps.

In 2006 he appeared with actor George Clooney at the U.N. Security Council to call attention to the humanitarian crisis in Darfur. That year he accompanied Oprah Winfrey on a televised visit to Auschwitz. In 2007 his foundation issued a letter condemning the denial of the Armenian genocide. The letter was signed by 53 Nobel winners. 2009 he accompanied Barack Obama and German chancellor, Angela Merkel on a tour of the Buchenwald concentration camp. That year he announced his support of the persecuted Tamil minority in Sri Lanka.

Wiesel was active in trying to prevent Iran from manufacturing nuclear weapons. He said: “The words and actions of the leadership of Iran leave no doubt as to their intentions.” He also ran ads in several large newspapers, in which he condemned Hamas for the use of children as human shields in 2014. Wiesel criticized Pres. Obama for pressuring Prime Minister Netanyahu to halt Israeli settlement construction in east Jerusalem. He stated: “Jerusalem is above politics. It is mentioned more than 600 times in Scripture–and not a single time in the Koran. It belongs to the Jewish people and is much more than a city.” In 2012 Wiesel protested against the whitewashing of Hungary’s involvement in the Holocaust and returned the Great Cross Award he had received from the Hungarian government.

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1986 he said: “I trust Israel, for I have faith in the Jewish people. Let Israel be given a chance, let hatred and danger be removed from her horizons, and there will be peace in and around the Holy Land.”

In 2012 he spoke out against the unauthorized Mormon practice of performing posthumous baptisms of Jews by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. This was after such a baptism was performed for Simon Wiesenthal’s parents and upon learning that Wiesel himself was being considered for a proxy baptism.

Wiesel suffered from heart disease, and died on July 2, 2016 in his home in Manhattan. He was 87. In June of 2017 the southwest corner of West 84th St. and Central Park West was named Elie Wiesel Way. It was on that block where he had his first home and family since losing both to the Holocaust.

He explained: “What is the Sabbath? Everything is different. When the poor don’t feel their poverty. Even the sick forget their sickness because of the Sabbath. Sabbath is not only a change of behavior; it’s a change of time. The time of Sabbath. And therefore actually at the end of any meal in the Sabbath what we sing is a song that we love to sing with our friends when we are sharing a meal for the Shabbat, and it’s the Harachaman.

He wrote: “None of us is in a position to eliminate war, but it is our obligation to denounce it and expose it in all its hideousness. War leaves no victors, only victims.”