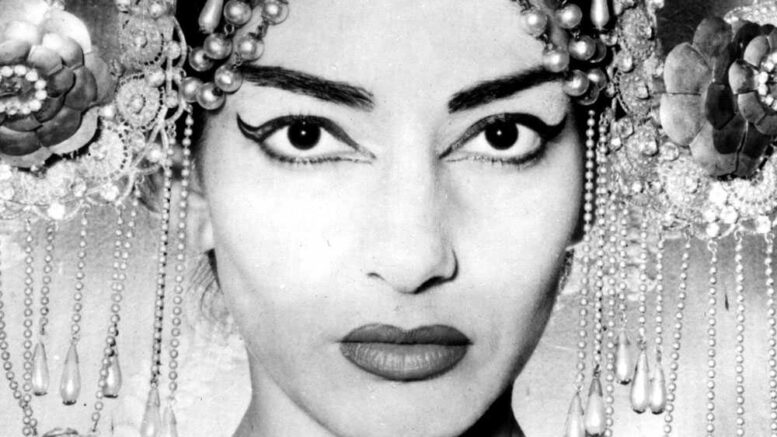

Maria Callas was born in NYC in 1923. Her parents were Greek immigrants and they lived in Washington Heights. Her mother returned to Greece with Maria and her sister when Callas was 13, and there she studied at the Athens Conservatory with Elvira de Hidalgo, a Spanish coloratura soprano who sang with Caruso and Chaliapin.

Hidalgo: “When I started teaching her she was the laughing stock of the whole conservatory…she was frightfully clumsy, fat, and ungainly…She was a glutton for advice and suggestions, and made every effort to take it all in and act on it as far as she could. The results were pitiful at first, but little by little she did begin to improve.”

To release her nervous tension, Callas worked harder than ever, spending most of each day at the conservatory or at Hidalgo’s apartment. She went to her teacher at 10 am for her lesson and stayed, listening to all the other voice students until eight pm. “I loved to listen to all those different voices: light soprano, lyric soprano, and the men too because I always believed that even the poorest voice can teach you something.”

Hidalgo remembered: “Always silent, almost scowling, she would sit in a corner and stay there until I had finished, in other words until the evening. She was there watching and listening while I took all my other lessons, and she learned all there was to be learned.”

Callas was happy to do exercises to train the agility of her voice to sing coloratura music. The soprano, Renata Tebaldi said that it was an incredible experience to hear Callas scale down her great big, huge voice to sing coloratura repertoire.

Hidalgo: “She put such force, such sentiment, such wonderful interpretation into all she sang. She would want to sing all the most difficult coloraturas, scales, and trills. Even as a child her willpower was terrific. She had a phenomenal memory and could learn the most difficult opera in eight days.”

Callas sang Norma more times than any other opera. She said: “Bellini’s opera Norma was used by Hidalgo as an exercise. So I remember I started learning Norma at the very early years of my schooling in music, many, many years before I sang it on stage.”

Hidalgo spoke about how near sighted Callas was, and that she couldn’t wear her eyeglasses on stage: “Maria Callas performed over 40 operas on stage without being able to see the conductor. In order not to miss her entries she memorized each of the entire operas, the parts of the tenor, the baritone, the bass, the chorus, everything. When she came to me at the conservatory she was already in the habit of learning the entire opera by heart.” In fact Callas trained her memory so well that she was able to practice without the music. “I learned for instance Norma and La Gioconda, so I could rehearse them in my mind, on top of a bus or walking in the street. There is a great deal to be done in the mind: you don’t always require a piano, nor to open your mouth. The poets talk of the mind’s eye: there is also the mind’s ear.”

She was an exceptionally quick learner. She considered solfeggio, the skill of being able to perform music at first sight, to be a singer’s most important training asset. She would pick up her part and devour it, and almost immediately sing it note for note. But the greatest of all her qualities, even then, was the expressive power she put into her singing.

Callas said: “It is so much hard work, so much love and so much devotion, but other people around you don’t see that, they think everything around you is just given to you.

“In Greece during the war it took six months of rehearsal to get an opera ready for the stage…how many sacrifices…at least you were well prepared. Whereas nowadays young singers are thrown out onto the stage just as they are without preparation, without knowing the opera well. After a few engagements they don’t take time to reflect: they immediately think they are great and famous, and that’s the beginning of the end.”

“I continued studying voice and piano with a kind of fury.” A friend remarked: “She practiced so hard and so intensively…that she would often spend more than ten hours a day practicing, which left her dead tired.”

Her mother recalled: “She practiced day and night and sometimes forgot to eat. Maria would refuse to leave her piano for meals, and I would bring them to her in her room. She would put the plate in her lap and go on working,”

Particularly impressive was her uncompromising self-critical approach to her work, remarkable in one so young. The conductor Yorgos Vokos stated that she was stricter with herself than her teacher was. “As a young girl she worked on her voice interminably, taking care over every detail.

“She had a brilliant ear. Whatever exercise her first teacher, Maria Trivella, played for her on the piano, she sang it almost right at the first go. We would hear Maria doing her vocal acrobatics—trills, runs, phrases, legati, staccato, scales—and every so often Trivella’s voice exclaiming, ‘Well done, Maria, well done!’ ‘But my passagework was terrible, my trills were only half there, my legati were awful. ‘But Maria…’ ‘No, no, I must do it again from the beginning! I’ve got to satisfy myself too. I’m sorry.’ So once more from the beginning, until Maria gave it her OK.”

At age 24 Callas said: “Everything I do, I am convinced I am doing it badly, and then I start feeling nervous and discouraged. Sometimes I get to the point of wanting death to release me from the torments and the anguish that constantly afflict me. I would like to give much more to everything I do.”

Callas first sang Tosca when she was only 18. She attended all of the orchestra rehearsals, and in this way studied the orchestration. She also requested private rehearsals with the conductor, who recalled: “You have no idea what a nitpicker she is! She drives you up the wall, always pestering you about the most trivial details. ‘Shall we go through it once more, Maestro?’ Whether you like it or not she makes you do it all over again! Whereas with the others you only have to mention the word “rehearsal” and they start looking at their watches!”

At age 20, having been cast in the role of Marta in the opera Tiefland, Maria shut herself in her room to study the role, and refused to open the door to anyone. From time to time her mother had gone in to bring her a drink or something to eat, and often found her asleep on the floor with the pages of the opera scattered around her. She showed up at the production’s first rehearsal with the entire opera memorized. She worked frantically to prepare herself, asked for extra rehearsals and begged the conductor to go through her part with her privately.

When asked what the word luxury meant to her, Maria said: “To me it means having a conductor who undertakes any number of rehearsals to produce a performance of high quality, and having musicians who work hard, without fixed hours. That’s the way people used to work once upon a time.”

Maria’s total dedication to her ambition of becoming a great singer was the one thing to which she clung desperately. “My life was my work and my work was my life.”

A friend remembered: “When we chatted on the way home, practically the only subjects we talked about were music and our future careers. She didn’t join in personal conversations. She was eternally absorbed in singing: nothing else interested her.”

Another friend said: “As if she could see a vision of her future, she paced nervously to and fro, saying over and over again with deep conviction, ‘Some day I’m going to make the big time! I’m going to get to the top.’”

She once said to her mother: “I’m going to be the greatest opera singer of them all. The whole world will be talking about me.”

A friend recalled “One day we were waiting for her in the living room while she got dressed in her room, and was singing something that reverberated throughout the apartment. Her mother shouted: ‘For heaven sake’s, stop! We’ve had enough, our heads are spinning; we can’t hear ourselves think!’ Defiantly, Maria answered from her room, ‘Mother, I’m going to be the greatest prima donna in the world!’ ‘Oh get lost!’ her mother retorted.

When she began singing with the National Theatre in Greece at age 17, some of her colleagues were jealous and felt threatened by her talent. They began trying to find ways to prevent her from appearing. “That American bitch that’s come in, what right has she got to be here, the fat cow, taking our performances away from us? Kick the American out! A foreigner’s got no business in our opera company. She’ll ruin the performances with her accent.” They stood in the wings while she was singing, laughing and pointing their fingers at her, keeping up a flow of loud whispers, including remarks about her fat legs, until she couldn’t go on singing. Callas would sob and cry in her dressing room. An older colleague advised her friends; “Tell her to give up the theatre! After all, the poor girl’s never going to get anywhere.”

Remembering what it was like in 1944 at the Greek National Opera, Maria said: “I got on my colleagues’ nerves. They were older people. I was young, they couldn’t understand why I was chosen for certain roles. I was always ready. I just studied and was ready, which is always my weapon, always being prepared. It’s a conscientiousness and love of my work.”

Hidalgo: “The attacks of her colleagues not only made her work harder, but taught her to be a warrior. She learned to be a fighter and survivor, not a victim.”

“I won’t let anyone stand in my way. If anyone tries, I’ll smash them, and I don’t care who they are!”

The jealousy of her classmates only confirmed her belief in her ability and made her feel strong and optimistic. She worked harder and more consistently than any of her fellow singers, with a fierce dedication and persistence. Through her faith in herself and her indomitable persistence, she survived the various trials and tribulations of those early years in Greece. During an eight year period in Greece she sang 56 performances of seven leading roles

“Everything I have achieved, I achieved by hard work.”

During her early years in Greece one conductor didn’t think Callas sang the opera Fidelio well. She said to him: “One day you’ll be groveling to conduct me!” Callas said to a conductor of the Athens Radio orchestra: “In a few years you will be begging me!” She also said this to the general manager of the Greek National Opera, to the general manager of the San Francisco Opera, and to the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera.

At 22 Callas returned to New York. She intended to sing at the Met. One of her colleagues asked: “What if they don’t give you an audition?” “Oh, then I’ll go there every day and sit on the doorstep. One day they will get fed up with me and give me an audition.”

“In 1946 in America I went from one movie house to another, not to see the films, but so as not to go out of my mind from torturous thoughts about my uncertain future.”

Finally she was invited to make her Italian debut in La Gioconda at the ancient amphitheatre in Verona. Even though her performances there were successful, she couldn’t get a job afterwards!!! No one in Italy would hire her, despite the most intensive efforts at promotion, including a recording she made of her best arias. Callas was frustrated.

Finally Tulio Serafin, who had conducted her at the arena in Verona, hired her in Venice to sing first Tristan und Isolde, and then a year later, Die Walküre. In the midst of the series of performances of Die Walkure, the soprano who was to sing Bellini’s bel canto opera, I Puritani became ill and Serafin decided that Callas would replace her, despite the completely different kind of voice required for the role. Amazingly, Callas learned Puritani in just one week while she continued performing Die Walkure! This feat earned her a ton of publicity and people have been marveling at her accomplishment ever since.

Her colleague, the soprano, Renata Tebaldi said that the most fascinating thing was to hear how Callas was able to scale down her enormous voice to sing bel canto repertoire. In fact, when she auditioned for Toscanini, he wanted very much to cast her as Lady Macbeth, because of the size and particular quality of her voice. Unfortunately, he retired soon thereafter and they never collaborated.

Callas said: “Conductors for us, once upon a time especially, were gods. We went to the theatre on tiptoes—it’s like going to church, really. That’s how we were brought up.”

Tulio Serafin had played viola in the La Scala orchestra under Toscanini in the early part of the 20th century and went on to conduct all over the world. He was an early mentor of Callas. She spoke about what she learned from Serafin: “I drank all I could from this man. He was the first maestro for me, and I am afraid he is the last man of his kind. Today they don’t take the trouble, they don’t have that much experience, they start too young and don’t have enough humility towards music. What I learned from Serafin is that you must serve music; it is our first and main duty.”

Callas observed how awkwardly many singers moved on stage, and swore that that would never happen to her. She bought a big mirror in which she would watch herself practicing, scrutinizing her every movement from head to toe and making sure she did not overact.

Callas married a successful Italian businessman, Giovanni Battista Meneghini in 1949. He was 28 yrs older than her. Meneghini gave up his interests in his family’s business to invest in and manage her budding career full time.

Callas wanted to do dramatic justice to the roles she played, so she decided to lose weight. When Callas saw Audrey Hepurn in Roman Holiday, she decided that that was her standard. She lost eighty pounds in less than a year. Suddenly she became glamorous!

As her career became that of a super star, she attracted the attention of the billionaire, Aristotle Onasis. They fell in love she left her husband of ten years, and began a widely publicized affair with Onassis, who was also married. He was 23 years her senior. The Law of cause and effect is very strict, because nine years later, Onassis left her and married Jackie Kennedy. 8 years before her death Callas said to a close friend: “I started dying when I met this man and gave up music.” The last role she sang onstage was Tosca.

Not long after this Callas’s voice deteriorated to the point where she had to stop singing in public. She tried acting in a movie. She tried stage directing. She gave the master classes at Juilliard. After several years, she tried to get her voice back and in 1973 and ’74 Callas sang a world concert tour with her long time friend and colleague, tenor, Giuseppe DiStefano, but her voice was only a shadow of what it once had been.

Having stopped singing in public, and with no one to share her love, Callas became incredibly depressed. She became addicted to sleeping pills, and during her last years, isolated herself, living with two servants in her Paris apartment. She could no longer sustain her interest in living. The last time she saw DiStefano she said to him “Everyday is one day less”.

Her last public performance was in Tokyo, on the world tour with DiStefano. Three years later she died of a heart attack at the young age of 53.