When conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboim joined philosopher Edward Said to establish the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, combining Israeli and Arab musicians, they knew it would be no magical bringer of peace. Instead, it was intended as a project against ignorance, giving space for opposing sides to understand one another and to disagree without “resort to knives”. For 24 years its achievement has been to show that mutual cooperation and respect can produce grace and beauty in a world too often defined by bloodshed and cruelty.

Students from the Middle East come to Berlin to study music with the star conductor Daniel Barenboim. Now the Israel-Hamas war is testing their ideals.

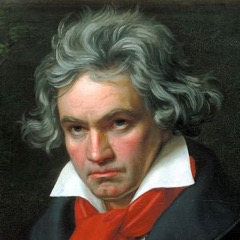

Mr. Barenboim, who has been scaling back his appearances, made time to rehearse and perform with the academy’s students this fall.

It was a recent afternoon at the Barenboim-Said Academy, a

sleekly modern music conservatory in Berlin founded by the

renowned Argentine-Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim with the

intention of bringing together students from across the Middle

East, and the musicians were wrestling with the Israel-Hamas

conflict and their raw emotions.

An Israeli music student described the trauma of the Hamas

attacks. A Palestinian spoke of feeling voiceless and vulnerable. An

Iranian described fears that violence could spread across the entire

region.

“It takes courage for you to be here,” Mr. Barenboim, 80, who has

worked almost 25 years in pursuit of the elusive goal of Middle

East peace, said from the podium. “We have to listen to each other,”

he declared, giving voice to what might be the academy’s unofficial

credo, both for music-making and politics.

The academy, like other peace projects, has long had to deal with

the volatility of the Middle East, navigating bursts of violence,

unrest and shifting politics.

But the Israel-Hamas war has tested these efforts in new ways, as

became clear during a visit to the academy earlier this month

when Mr. Barenboim and the students were preparing for their

first concert together since the fighting began. The scale of the

conflict, the rapid spread of images of death and destruction on

social media and the ubiquity of misinformation have made it

harder to promote civil debate and to find common ground.

In an environment where Israelis, Palestinians, Iranians, Syrians,

Egyptians, Lebanese and others study and live together, the war

has prompted a reckoning. Some students, after heated debates

with classmates over who is to blame for the carnage, have

questioned whether they should even play music together in a time

of war. Others say that music has brought them closer.

“We will not bring peace, and we will not solve the world’s

problems, as much as we might want to,” said Katia Abdel Kader,

23, a Palestinian violinist from Ramallah who is in her fourth year

at the academy, which offers music degrees and courses in the

humanities. “But we create a space, and that’s what is missing in

the world, not only in the Middle East. Places for people to be

accepted by the other.”

Itamar Carmeli, 22, a pianist from Tel Aviv who is in his third year,

said it was impossible to escape the conflict because “our families

are there and our childhood is there.” He said he had learned to

accept his classmates’ views even if he disagreed with them, partly

because music had taught him to listen more deeply.

“There is no harmony,” he said, “without dissonance.”

The current conflict has even tested the idealism of the school’s

founder, Mr. Barenboim, who founded

the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra in 1999 to bring Israeli and Arab

musicians together.

The academy, which is rooted in the same principles as the Divan,

now has 78 students — about 70 percent from the Middle East and

North Africa — who study in a well-appointed building in the heart

of Berlin that opened in 2016; its concert hall was designed by

Frank Gehry.

Mr. Barenboim, a titan of classical music who led the Berlin State

Opera for three decades before stepping down this year, has

drastically reduced his commitments because of a serious

neurological condition. But he has made a special effort to be with

the students in recent weeks for rehearsals and discussions.

The academy, which opened in 2016, has quotes about peace by the philosopher Baruch Spinoza on its glass

doors; practice rooms; and a vibrant humanities program.

In an interview after a recent rehearsal, Mr. Barenboim said he

worried the latest war could morph into a “world catastrophe” in

the absence of more efforts to bring Israelis and Palestinians

together.

“There’s no use saying, ‘We the Jews have suffered more than

anybody else,’ or the Palestinians’ saying, ‘We suffered more than

all of you,’” he said. “This has been a very difficult century with

little rest. I think we have to keep going, and forget our own

positions, and get along with a sense of equality.”

The school year at the Barenboim-Said Academy began this month

with the usual orientation sessions on Israeli-Palestinian tensions,

how to respect differences and ways to see beyond stereotypes.

Then came the deadly Hamas-led attack on southern Israel on Oct.

7 and the ensuing Israeli strikes on Gaza. Many students, their

phones buzzing with frantic messages from friends and relatives

and displaying images of devastation, were too disturbed to

practice their instruments. The school’s leaders, including Regula

Rapp, the rector, and Mr. Barenboim’s son, Michael, who serves as

dean, brought in counselors fluent in Hebrew and Arabic.

The students made a point of checking in with each other, and they

organized meetings to try to work through some of their

differences. Unsure of what to say, they sometimes offered only

hugs. At one point, they gathered for a start-of-the-semester

dinner, sharing homemade dishes: hummus, baba ghanouj, labneh

and bulgur salad.

Their conversations were sometimes tense, as musicians from

Israel spoke of losing a sense of security and the Palestinians

described life under the suffocating blockade Israel has imposed on

Gaza for 16 years. The conversations were also deeply personal,

with some students sharing stories of losing loved ones during

decades of violence in the Middle East.

The students tried to support each other as they faced new

difficulties in German society; the authorities banned many pro-

Palestinian gatherings, and a synagogue in Berlin was attacked

with firebombs. They met at their dorms or went out for beer and

cigarettes and talked about how they felt guilty being away from

their families.

Roshanak Rafani, 29, a percussionist from Tehran who is a member

of the student government, said the tumult in the region could be

shattering; she has at times contemplated abandoning her studies.

“Imagine that people are dying, and now I’m just practicing to see

which hand I should put here or there,” she said. “We all feel this

inner conflict.”

She added that the young musicians had gotten beyond their

differences by embracing the idea that “we’re all students, and

there is no side now for us here.”

“We’ve all accepted the fact that we cannot really convince each

other about many things,” she said. “People talk and raise their

voices and yell and cry, but two hours later, they are hugging each

other.”

The war has hung over classroom discussions as well.

In a recent philosophy class, the topic was Plato’s allegory of the

cave, a metaphor for contemplating the divide between ignorance

and enlightenment.

Mr. Barenboim’s efforts have not been without controversy. His

projects have been denounced by Israelis and Arabs alike, and

musicians in the Divan sometimes face displeasure from their

families.

But Mr. Barenboim, who has described his work as not political but

as a “project against ignorance,” said he was confident that the

Divan orchestra and the other programs would endure, even if he

was no longer at the helm.

“No question,” he said. “Otherwise I wouldn’t be doing it. But it’s

not easy.”

Mr. Barenboim is visibly weaker now. But there are still flashes of

his spirited self at the podium, as when he chastised the students

the other day for fumbling a bit of Beethoven: “Do you want me to

buy a metronome for everybody?”

Or his rejoinder to a horn player who complained that he was tired:

“At your age, you’re tired? I’m 80 years old, and I would never say

in company like this, ‘I’m tired.’”

In the days leading up to the academy concert last week, the

strains of the war were evident.

Some Palestinian students were having doubts about performing,

concerned that they would project an aura of harmony at a time of

deep division and suffering. But after prolonged debate, they

decided it was important to embrace the spirit of the institution,

announcing their decision to Mr. Barenboim at rehearsal.

At the concert, the student body released a statement making clear

that they all had felt the impact of the war.

“Our hearts are heavy; our minds are elsewhere with every single

person affected by the devastating situation in Palestine and

Israel,” the students said in the statement. “May our music bring us

together, may it heal a little piece of our hearts.”

When Mr. Barenboim took the stage to lead works by Prokofiev,

Wagner and Beethoven, he praised how “wonderfully and

generously” the musicians played together before asking for a

minute of silence.

“The situation is inexplicable, and my words cannot change it,” he

said. “But we are happy to perform for all of you today.”

After their performance, and a standing ovation, the students

embraced onstage. (A few days later the war would enter a new

phase, with Israel beginning its ground invasion of the Gaza Strip.)

Mr. Carmeli, the Israeli pianist, recalled before the concert that he

had not spoken to Ms. Abdel Kader, the Palestinian violinist, for 18

months after joining the academy. But when he heard her play, he

approached her and discovered that they had once lived only about

20 minutes apart.

“The landscapes and the smells and the tastes and the flavors that

we grew up on is all shared,” he said.

Ms. Abdel Kader said the experience of getting support in a

difficult time from “the other side — the side you learned to hate”

had moved her.

“Now is the time to remove the walls and look at each other,” she

said. “The moment you just look in someone’s eyes and you

understand we’re just the same — that’s what matters for me.”

Based on articles by Stephen Pritchard (the Guardian) and Javier C. Hernández (New York Times)