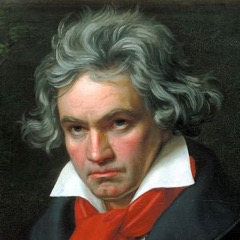

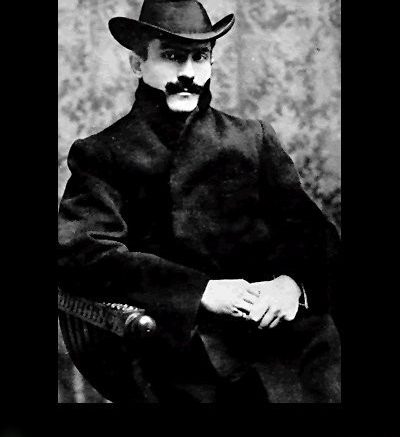

Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini’s (1867–1957), career spanned an incredible 69 years as head of La Scala, the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic, and the NBC Symphony. He conducted the world premieres of Barber’s Adagio for Strings, I Pagliacci, La Boheme, The Girl of the Golden West, and Turandot. Toscanini had a photographic memory, conducted over 600 compositions from memory, and raised the standards of orchestral and operatic performance.

Toscanini’s love for Wagner’s music began in his youth. When he was 17 he played cello in a production of Lohengrin, and was so moved that he wept. At age 21 during a performance of Tristan und Isolde Toscanini abandoned his ambition to be a composer.

He opened his first season as artistic director of the opera theatre in Turin with Götterdämmerung in 1895 and included Wagner’s music on his first ever symphony concert in 1896. His first and last appearances at La Scala were with Wagner’s music. Toscanini’s first rehearsal at the Metropolitan Opera was of Götterdämmerung. His first and last concerts with the New York Philharmonic included Wagner’s music. Toscanini conducted the first ever symphony concert on TV in 1948: an all-Wagner program. The Meistersinger Prelude was among the compositions Toscanini conducted most frequently in symphonic concerts; and in his home in Milan, the maestro kept a death mask of Wagner near his piano. His last performance of his career was with an all-Wagner program.

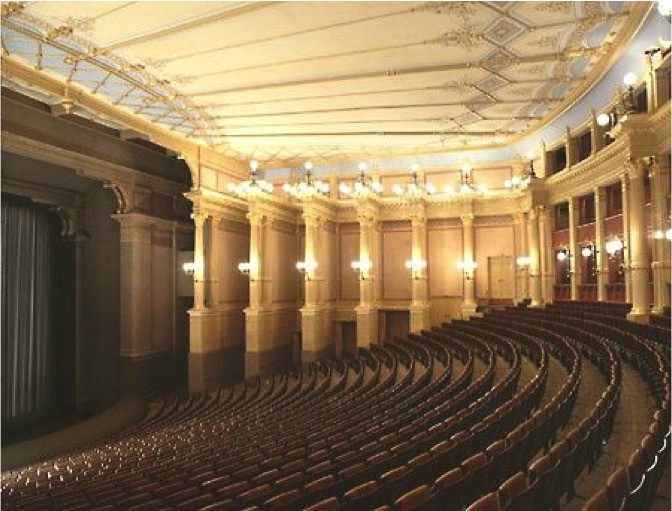

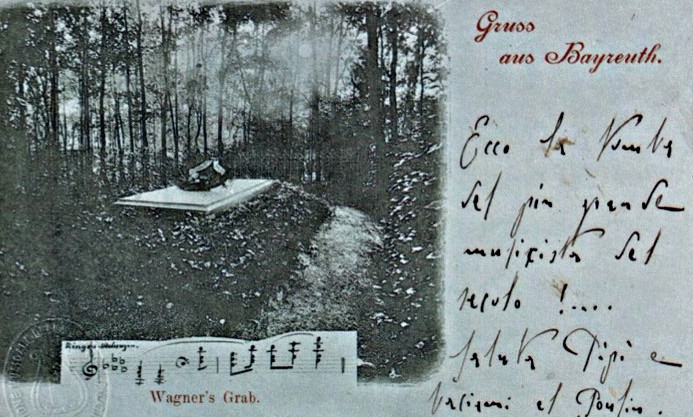

Toscanini refused to appear in countries where Fascism and authoritarianism prevailed. Understanding the centrality of Wagner’s music to Toscanini is key to appreciating his boycott of Bayreuth, Germany, where Wagner designed and supervised the construction of a theatre with magnificent acoustics, built for the exclusive performance of his operas. In 1895 Toscanini attended performances there, and when he visited Bayreuth again in 1899 the maestro sent his brother-in-law a postcard of Wagner’s grave, on which he wrote: “Here is the tomb of the greatest composer of the century.”

Toscanini’s postcard of Wagner’s grave

Siegfried Wagner, the composer’s son, was astounded when he heard Toscanini conduct Tristan und Isolde at La Scala in 1901. However, the conductor had to wait 29 years until Siegfried overcame strong opposition to inviting a non-German school conductor to perform at Bayreuth. The tenor Lauritz Melchior remembered that in 1930 when Toscanini finally made his Bayreuth debut “Arturo came as a pilgrim; Wagner was his pope,” and that “he wept the first time he stepped inside the theatre.

The Wagner family considered Toscanini to be the best of all conductors. Toscanini conducted again at Bayreuth in 1931 and agreed to conduct at the 1933 festival. However at the end of January, 1933, the devil incarnate became chancellor and immediately began destroying democracy in Germany. Toscanini was greatly alarmed and on April 1st sent a telegram to Hitler protesting the boycott of Jewish musicians and the dictator’s racist policy. This was published on the front page of the NY Times.

Two days later Hitler wrote to Toscanini, inviting him to Bayreuth that summer and expressing how much he was looking forward to personally greeting him. Toscanini responded indicating that this was not likely to happen, and he informed the Wagner family that he would not be returning to Bayreuth. Several years later he referred to giving up conducting in Wagner’s theatre as “the deepest sorrow” of his life. He never set foot in Germany again.

Wagner’s granddaughter, Friedelind Wagner, was strongly influenced by Toscanini’s anti-Fascist and antiracist attitudes and soon became an anti-Nazi renegade in her family.

At that time Toscanini was the most famous musician in the world, and his refusal to return to Bayreuth attracted international attention. He knew that by performing in non-nazi Austria, he could make a stronger protest against Hitler and therefore began conducting the Vienna Philharmonic until Hitler invaded Austria. After WW II Toscanini agreed to return to the Vienna Philharmonic on the condition that the musicians who were still Nazis be removed from the orchestra. The conductor’s demand was not met and he never conducted the Vienna Philharmonic again.

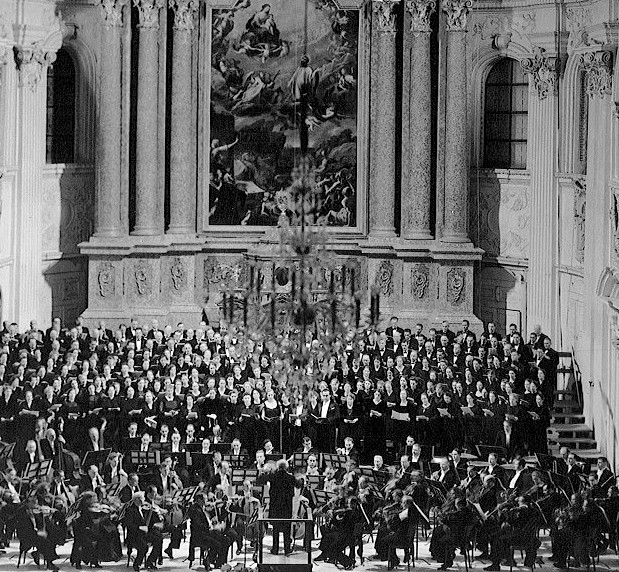

In 1938 Toscanini helped launch the Lucerne Festival in neutral Switzerland, conducting an orchestra largely composed of Jewish refugees, to which he returned in 1939 and 1946.

In the mid 1930s the Polish violinist Bronisław Huberman founded the Palestine Symphony, an orchestra, comprised of Jewish refugee musicians escaping Nazi persecution. Toscanini traveled at his own expense to Palestine in December of 1936, trained the orchestra, and conducted gratis, the first concerts of what is now known as the Israel Philharmonic. He said: “I had to show my solidarity.”

Toscanini stayed for more than a month and included the music of Felix Mendelssohn, because the composer was Jewish and Hitler had banned the music of Jewish composers from German concert halls. While there Toscanini experienced what he called “a continuous exultation of the soul.” He called it the land of miracles, where Jews who had been doctors, lawyers, and engineers in Germany had become farmers who transformed sand dunes into olive and orange groves.

Petah-Tikvah

Toscanini said it was difficult for him to speak because of the power of the impressions he had received, and his wife wept openly. She wrote to their daughter, “When we left we were both crying. If you stop to think of what they have achieved through sheer labor, it is nothing short of miraculous.”

Three months later, he wrote in a letter: “I would like to spit poison in the face of all mankind… I think of those poor young men who are going off fooled or forced to get themselves killed, not for their country, but for delinquents named Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin.”

Chaim Weizmann — who later became the first president of Israel tried to convince Toscanini to cancel his 2nd visit to Palestine, explaining that there was an increased danger of an Arab attack. Undeterred, and convinced that his visit would greatly encourage the young Jewish refugees, Toscanini returned to conduct the orchestra in April of 1938, again at his own expense. Fortunately, the maestro and his wife escaped a bomb thrown at their car.

While in Palestine, the dictator, Benito Mussolini announced his anti-Semitic policy in Italy, adopting German racial laws that deprived Jews of their citizenship. Toscanini referred to the policy as “medieval stuff”.

Mussolini decreed that all Italian theatres were to prominently display photographs of himself, and that the Fascist anthem was to be played before each performance whenever a high government official was in attendance. In 1931 Toscanini was attacked and beaten in the face by a group of Fascists for refusing to conduct the Fascist anthem. Mussolini then ordered the confiscation of Toscanini’s passport.

Toscanini wrote about the beating: “The lesson which they wanted to teach me was to no avail because I would repeat tomorrow what I did yesterday…The conduct of my life has been, is, and always will be the echo and the reflection of my conscience — reinforced by a proud and scornful character, yes, but as clear as crystal and just as cutting — always and everywhere ready to shout the truth loudly…Truth we must have at any price, and freedom of speech, even if that price should be death, I have said to our Fascists time and again: You can kill me if you wish, but as long as I am living I shall say what I think.”

He often spoke out against Mussolini, calling him a tyrant and a criminal. As a result, the maestro’s house was placed under 24-hour surveillance, his telephone was tapped, and his incoming and outgoing mail was read. In 1938 his passport was again confiscated, and when it was returned, he left Italy and did not return until after World War II.

Toscanini remained in exile in the United States conducting huge benefit concerts for the war effort and several charities. The Toscanini family also assisted a large number of Jewish refugees from Europe in securing American entry visas, jobs and homes. And he conducted the music of several Italian Jews.

After the war Toscanini insisted that the Jewish musicians at La Scala who lost their jobs in 1938 be reinstated.

The Buddhist philosopher, Daisaku Ikeda wrote: “Toscanini was not able to separate art from daily life. For him, pretending not to see injustice was not only stifling to his humanity but fatal to his art. As he said: ‘When one’s spirit is twisted, one’s backbone is twisted as well.’ It was Toscanini’s solid conviction that his daily actions must reflect his conscience… His heroic achievement served as an example to others.”

For more info my website: https://cesarecivetta.com and here is the link to more about my book and how to purchase The Real Toscanini: Musicians Reveal the Maestro, which is based on 50 interviews with musicians who worked with him: http://therealtoscanini.com