by Moshe Denburg

The Three Streams of Jewish Music – reprise

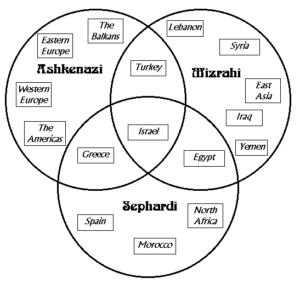

Here is a brief reprise of the main conceptual framework of the discussion of the Many Worlds of Jewish Music, namely, The Three Streams of Jewish Music. Have a look at the following graphic, which is a historical atlas, as it were, of Jewish Music.

We can describe Jewish Music as having three distinct streams. One is the Ashkenazi, or Western stream. This includes Klezmer, and is music originating in Eastern Europe and extending to the rest of Europe and the Americas.

The second stream is the Sephardi, which refers to Mediterranean cultural sources, including Spain, Portugal, North Africa, Greece, and Turkey.

The third stream is the Mizrahi, literally Eastern, and refers to the music of Jewish people who resided over the centuries amidst Arabic and other Middle-Eastern cultures.

As you can see, these three streams are not completely separate, but do in fact intersect in many places.

The Ashkenazi Stream includes the music that originated in Eastern Europe and moved westward and northward throughout Europe and later into North America. The language most associated with this stream is Yiddish, a unique hybrid of Medieval German and Hebrew. And the instrumental style of music most associated with this stream is Klezmer.

The Sephardi Stream refers to music that originated around the Mediterranean, and the Hebrew word ‘Sephardi’ literally means Spanish. This alludes to the fact that until the Spanish expulsion of all non-Christians in 1492, a very fruitful Jewish culture existed in Spain, and these Jews developed a spoken language of their own, called Ladino. Ladino, based on the 15th-century Spanish that they spoke before the expulsion, forms the basis of much Sephardi repertoire.

The Mizrahi Stream is the music of Eastern Jews, from the Eastern Mediterranean and eastward into Asia. ‘Mizrahi’ literally means ‘Eastern’. This music is the child of the interaction between Jewish people and the cultures of Arabia, Turkey, and Persia. Generally, this encompasses the following countries: Israel, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, and as far east as India. In song, the main language used is Hebrew, though local languages have also been used, most notably, Arabic.

It is important to note, that The Three Streams idea is a snapshot in time, and does not depict an unchanging situation. Things are evolving all the time. But the concept gives us a good starting point for the study of Jewish Music today.

Music of the Synagogue

This topic, to my mind, is the very essence of Jewish Music. In fact, it is so central to understanding Jewish Music in its traditional sense that we have decided to deal with this section in a much fuller manner in a separate presentation. For now, we will touch upon this topic to give the listener a sense of Jewish music in its home context.

In the Synagogue, two main musical traditions have developed over the centuries, namely:

Biblical Cantillation, which is the chanting of the Torah, the holy scriptures, and

The Modes of Prayer, or the melodic settings of the prayers.

In addition, the services are enhanced by Congregational Singing. In fact, this is seen as the best way to get congregants involved in the services. The interesting thing about Congregational Singing is that melodies can be brought in from the outside world, even the secular world, and prayers are set to these tunes. Thus, they are instantly recognizable, and the congregant feels at home.

The Intercultural Synthesis

In the three streams diagram, serendipitously or deliberately, Israel is to be found in all three. It is the only geographical area that finds itself sharing all three streams.

This reflects the overall trajectory of Jewish cultural experience over the last two millennia. The in-gathering of the Jewish people in the land of Israel gives expression to all the varied cultural experiences that Jews brought with them from the lands of their dispersion. The commonality of Jewish diasporic experience has always been our desire to participate in the cultures surrounding us, contributing to them, and integrating them into our own practices.

In Israel, this integration has been heightened and has rendered some unique music. Early Israeli music is replete with instances where Yemenite (a Mizrahi culture) melodizing and the Ashkenazi system of harmony and orchestration come together. To me, this has always been a true intercultural synthesis.

To be honest, for many years, the Ashkenazi culture was ascendant in Israel; perhaps this was because modern Zionism was born in Europe, and in general, European cultural expression was ascendant in much of the world when Israel was founded. Today, the Mizrahi manner of singing and playing is front and center in Israeli culture. But the early experiments are a great example of how Jewish music is an intercultural phenomenon.

Cultural Interplay in North America

Tearing ourselves away from all this heavy intercultural synthesis, let’s have something completely different. As was alluded to plenty in the presentation, Klezmer: Jewish but not Too Jewish, another kind of synthesis is one in which the Jewish musician laughs at himself regarding his early predicament in America, of being the outsider wanting in. One great exponent of this conundrum in song was Mickey Katz, with his Yinglish workups of a lot of American chestnuts, such as She’ll Be Comin Round the Katzkills (aka She’ll Be Comin Round the Mountain), HaimAfen Range (aka Home on the Range), and Borscht Riders in the Sky (aka Ghost Riders in the Sky), to mention but 3 of his innumerable tongue in cheek parodies.

Early in part 1 we alluded to songs that marry the Yiddish language with a swing rhythm. There are other intercultural marriages that have been happening as well. Songs that utilize well-known folk songs in English and create new Hebrew lyrics for them are examples of this kind of synthesis.

The intercultural synthesis is going on everywhere today, in Jewish music and in general. In North America, just as in centuries past in other countries, the melodic structures of folk music are being utilized in Synagogue song. One excellent exponent of this contemporary integration is the late singer/songwriter Debbie Friedman, who has contributed many melodies for significant prayers that are part of the Synagogue services. Her melodies are not in the traditional modes or melodies of prayer, but rather resemble American folk song. Songs like these are playing a more and more important role in preserving the Jewish tradition, as they permit the congregant to join in the Hebrew liturgy, by introducing melodies that are both uplifting and musically familiar.

Going in the opposite direction, we can cite the seminal song by Leonard Cohen, Hallelujah, a staple of the English language world’s musical expression, taking a serious Jewish conception and bringing it to general public awareness for Jews and non-Jews alike. I consider this song as a kind of update of the Song of Songs, a book of the Biblical Canon that speaks of erotic love unabashedly.

Finally, going from the sublime to the irreverent, there is Kinky Friedman, who, with songs like They Ain’t Makin Jews Like Jesus Anymore, delivers a more ‘in-your-face’ hit of Jewish-Americana.

Deliberate Synthesis and Today’s Intercultural Context

Now to get back to the subject of Intercultural Synthesis in earnest, I would point to the very deliberate intercultural constructions happening nowadays. Over the past 150 years or so, the West and East have been learning more about each other, first via scholars who brought religious and other texts from one part of the world to another, and then, gradually, in the 20th century, the actual sharing of the arts. This has only accelerated in the 21st century, with global access now at our disposal via the internet and widespread travel.

If I may share my own experience and artistic trajectory, for many years I sought an opportunity to create a large-scale intercultural project. This eventuated, in 2001, with the founding of the Vancouver Inter-Cultural Orchestra (VICO). Now there have been other large-scale projects, some quite ad hoc, like Ravi Shankar’s sitar concertos, and some more established, like YoYo Ma’s Silk Road Project.

My own compositions created for the VICO have often been based on Jewish texts. This is a deliberate attempt, on my part, to utilize the larger world as a musical palette to present matters of Jewish sensibility and tradition.

Making Intercultural Music with Jewish Musical Elements

There are always several ways to begin to refer one type of music or cultural tradition to another. To my mind, the first, most obvious feature of any culture is language. The language of Jewish people everywhere has always been Hebrew. This is the language of prayer, of the Bible, and of poetry and literature throughout the ages. Even though Jewish people have lived with, and contributed to many other languages, and created their own dialects in these, the one unifying language, written, chanted, sung, and – for the last 100 years especially – spoken, is Hebrew. Thus, taking as a point of departure a poem, or a prayer, in Hebrew, one can begin to construct an intercultural work which may incorporate many other cultural references, including instruments and techniques.

Another way is to utilize the modes, the melodic structures of Jewish music, and adapt them to the various instruments one is writing for. Modes very much capture the ‘soul’ of a people, and yet there are many Jewish modes that have commonalities with modes of other cultures. A mode is a home where a melody is born; and a melody is a universal musical common denominator. Thus, modes are a time-honoured way any culture borrows tunes and ideas from another.

Intercultural music-making is about the composer and the musician attempting to incorporate into their work something that does not exist in their own culture.

To summarize, intercultural music is a process whereby the main ingredients of one culture’s music are varied and mixed with the ingredients of another musical culture. These ingredients may include melody, rhythm, harmony, instruments, ornamental techniques, scales, and modes.

The Many Worlds of Jewish Music – Conclusion

Jewish Music is many things, but historically it is the music of the wanderer, taking from and contributing to many cultures, while preserving Jewish identity. Today things are changing in two ways:

- Israel has become a geographic center for integrated Jewish cultural expression;

- The global access to many cultures, facilitated by the internet and travel, has made possible many intercultural collaborations which are giving rise to many new musical hybrids and experiences.

Central to understanding Jewish Music is the 3 streams idea. Of course, it is mainly a historical-geographical snapshot of where Jewish music comes from, it is not a permanent construct. But it clearly illustrates the intercultural synthesis idea, how Jewish music is varied, with great potential for the creation of many new worlds.

The Many Worlds of Jewish Music – part 2

Important Notice

The Many Worlds of Jewish Music

is a non-monetized presentation,

created exclusively for educational purposes.

Music Credits

Ani Ma-amin – movement V

(I Believe)

by Moshe Denburg

Vancouver Inter-Cultural Orchestra

and Laudate Singers

Lars Kaario, conductor

Russian Sher

Traditional Klezmer Repertoire

Performed by Tzimmes

Cuando El Rey Nimrod

(When King Nimrod)

Traditional Ladino Repertoire

Arranged by Moshe Denburg

Performed by Tzimmes

Adon Has’lichot

(Master of Forgiveness)

Text: Hymn for the concluding service

on Yom Kippur

Music: Traditional Mizrahi Repertoire

with additional music by Avishai and Itzik Eshel

Adon Olam

(Ruler of the Universe)

Text: Traditional Synagogue Liturgy

Sung to the tune of Jingle Bells

by James Lord Pierpont

Performed by Moshe Denburg

Yesh Li Gan

(I Have a Garden)

Text: Chaim Nachman Bialik

Music: Nachum Nardi

Adapted from a traditional Syrian melody

Performed by Bracha Tzfira,

accompanied by Nachum Nardi

Shnei Shoshanim

(Two Roses)

Text: Yaakov Orland

Music: Mordechai Ze-ira

Performed by Shoshana Damari

Bo-i

(Come With Me)

Music and Words: Idan Raichel

Performed by the Idan Raichel Project

Eize Yom Tov

(A Good Day)

Music: Idan Raichel

Lyrics: Idan Raichel and Tamar Yahalomi

Performed by Nasrin Kadri and Idan Raichel

Tisma-ani

(Hear Me)

Lyrics: Amir Abu, Tamar Yahalomi,

Yonatan Kalimi

Music: Tamar Yahalomi, Yonatan Kalimi

Performed by Nasrin Kadri

Modeh Ani

(I Give Thanks to You)

by Avi Ohayon and Asaf Tzruya

Performed by Omer Adam

Y’ladim Ze Simcha

(Children Are Happiness)

Lyrics: Yehoshua Sobol

Music: Shlomo Bar

Performed by Shlomo Bar and Habreira Hativ’it

She’ll Be Comin Round the Katzkills

Based on She’ll Be Comin Round the Mountain

Adapted by Mickey Katz

with additional texts and music

Rahav Hayam

(Wide is the Ocean)

Music: Traditional Folk Repertoire, ‘O Waly Waly’

Hebrew Lyrics: Moshe Denburg and Simon Ophir

Performed by Tzimmes

Mishebeirach

(The One Who Has Blessed)

Text: Liturgy of Jewish Prayers

Music: Debbie Friedman

Performed by Debbie Friedman

Hallelujah

Music and Words by Leonard Cohen

Performed by Leonard Cohen

They Ain’t Makin’ Jews Like Jesus Anymore

by Kinky Friedman

Performed by Kinky Friedman

and the Texas Jewboys

Ahavat Hadasa

(The Love of Hadasa)

from Dreams of the Wanderer by Moshe Denburg

Vancouver Inter-Cultural Orchestra

Lars Kaario, conductor;

Amir Haghighi, tenor soloist

Capilano College Singers,

Capilano College Festival Chorus,

Cecilia Ensemble Women’s Choir

Dror Yikra

(He Shall Declare Freedom)

Text: Dunash Ben Lavrat (10th Century)

Music: Traditional

Performed by Tzimmes

Ani Ma-amin – movement V

(I Believe)

by Moshe Denburg

Vancouver Inter-Cultural Orchestra

and Laudate Singers

Lars Kaario, conductor

Debka Hasid

Music: Traditional and Original

Adapted and Arranged by Moshe Denburg

Performed by Tzimmes

Resources on Jewish Music – https://www.tzimmes.net/jewish-music/overview