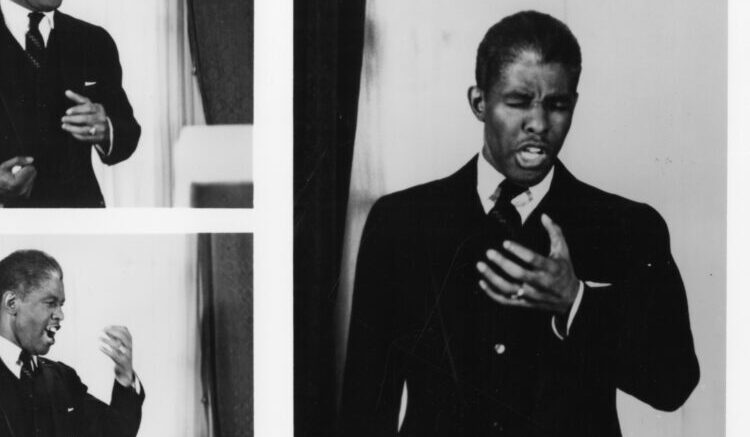

Once known as the “Black Caruso,” during his 60–year career, Roland Hayes packed concert halls all over Europe, South America, and the United States. At the height of his popularity, he sold out famous venues such as Carnegie Hall, Washington’s Constitution Hall, Boston’s Symphony Hall, Covent Garden and Wigmore Hall in London, and the Hollywood Bowl. He was the first African American musician to perform with a major symphony orchestra in the U.S. He sang for crowned heads of Europe, prime ministers, presidents, and other heads of state.

His trail-blazing career carved the path for Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson, Todd Duncan, Dorothy Maynor, and many others. He was also one of the first concert artists to program spirituals on his recitals.

Roland Hayes was born in 1887 in Curryville, Georgia, where his mother, Fannie, had once been enslaved. When Roland was 11, his father died, which resulted in his mother becoming a single parent. She then moved the family to Chattanooga, TN. With his brother Robert, Roland began singing in the Silver-Toned Quartet for nickels, dimes and quarters. At 14, Roland, who only went as far as 5th grade, began working in a metal foundry. One day he got pulled into the machinery by the conveyor belt, and he was brought home in a full–body cast. It took 10 weeks to recuperate. “I could not understand how I had come out of it alive. I quite simply believed that my escape was miraculous. God had spared me, I thought, to work out in me some mission. I have never entirely lost since that time the feeling that I have had a heavenly vocation to fulfill, although I did not know then that I should make a ministry of music.”

Hayes began taking two voice lessons a week with organist and choir director, W. Arthur Calhoun. He played young Roland the recordings of Nellie Melba and other great singers, but when he heard a recording of Enrico Caruso singing I Pagliacci, Hayes said: “That opened the heavens for me. The voice of Caruso seemed to me to come from some remote and inaccessible heaven where a kind of light shone. My dormant senses were awakened by Caruso’s matchless tones.” Caruso’s influence is quite evident in his recording of I Pagliacci from 1918.

Roland’s decision to become a great singer became his life’s work, and from that point on, he pursued it with missionary zeal. However, Roland’s mother wanted him to become a preacher. She was opposed to his musical aspirations and said:

“They tell me Negroes can’t understand good music, and white folks don’t want to hear it from us. So it seems to me you are making a mistake.”

Nevertheless, in 1905 – at age 18 – he left home with $50 of his savings and went to Nashville, TN, where he became a student of Jennie Robinson, the head of the music department at Fisk University. While there, Roland worked odd domestic jobs, and formed another vocal quartet to earn extra money. Miss Robinson didn’t approve of his singing outside of school, and after 4 years, kicked him out of Fisk. Roland then moved to Louisville, Kentucky, where he worked as a waiter, and did some singing at private dinners and at movie theatres for silent films. He also sang with the Jubilee Singers, who toured extensively in the U.S. and Great Britain to raise money for a new campus for Fisk University. When the group performed in Boston, Roland decided to stay in Boston. While there, he auditioned for 5 voice teachers. Each of them believed that it would be impossible for a Black man to be accepted as a serious artist. “I was determined not to be permanently put down.” He began voice lessons with Arthur Hubbard. However, the lessons took place at Hubbard’s home in the suburbs to avoid embarrassment if Roland were to be seen in his teacher’s studio by his white pupils, many of whom were from the South.

While studying voice, Hayes worked as a page boy for the John Hancock Insurance Co., and moved his mother from Chattanooga to live with him in Boston.

In 1912, Roland met the baritone and composer, Harry T. Burleigh. They formed a successful vocal quartet that sang in Carnegie Hall at a concert attended by former president Teddy Roosevelt. Roland also sang at various churches, and in 1914, made a concert tour of several Southern states. He also formed the Hayes Trio with William Richardson and William Lawrence, and they toured Pennsylvania’s Chautauqua circuit. Because of racism, Roland couldn’t get a manager, so he continued advertising his services and sang many concert tours, but always lost money after paying the rental fees for the venues, and the fees for his pianists and other performers he appeared with. Finally, Hayes decided to sing a big concert in Boston in 1917, and to rent Symphony Hall, home of the Boston Symphony with a seating capacity of 2,600! This was against the advice of his teacher and most of his friends. In fact, when he asked the wife of the governor of Massachusetts to be a backer, she refused, saying: “I cannot let my name be attached to an enterprise which is bound to be a failure before it begins.” A music critic wrote negatively about the plan, which resulted in protests from Boston’s music-loving public. Hayes hired a secretary to compile a mailing list of 3,000 people to send flyers to, and Hayes actually used a telephone directory, from which he chose names at random to call and promote the performance to.

Roland spent the next 2 years giving concert tours throughout the U.S. to raise the money for the performance. He paid the hall’s $400 rental fee well in advance, saying: “Nothing now could stop me from doing as I pleased.” The result was that the concert was completely sold out, and several hundred people had to be turned away at the door.

No record label would give him a contract, so he hired Columbia Graphophone Co., renting their studios and hiring their technicians to create his own recordings, which he then advertised and distributed himself.

In 1917 Hayes brought his mother along on a transcontinental tour of the U.S. with the pianist, Lawrence Brown, who later became Paul Robeson’s pianist. The tour lost money, but undeterred, they made another tour the following year. Since no manager would take on a Black artist, Roland negotiated the contracts, and managed all of the promotion and his performance fee collections in each city himself. And he had difficulty getting paid for some of the concerts, which led him to <demand in future contracts that he was to be paid in advance of each performance.

In the spiritual Deep River, the words “I want to cross over campground”, over the Jordan River, is a metaphor for the enslaved people in the United States crossing the Ohio River to freedom in the North.

In 1920, at age 32, Hayes and Lawrence Brown departed for London. There, he continued managing his own performances, which consistently lost money. After his first important recital at London’s Aeolian Hall, one reviewer wrote that it was “a sacrilege that a black man should sing the love songs of white people.” Roland then decided to give a performance at London’s prestigious Wigmore Hall. By then, he had secured British managers, but he still had to pay to rent the hall. On the day of the concert, Hayes came down with pneumonia and was running a high fever. His doctor ordered him to cancel the performance, but he refused. Upon arrival at the venue, he was so weak that he had to be carried up the stairs. He wrote about the beginning of the performance: “As I sang, strength came. Perspiration fell from me almost like rain. I sweated out all the pneumonia. At the end of the first group of songs, I walked off the stage alone like a man in a trance. When I returned to the stage for the second group, I had no feeling of sickness or infirmity.”

Hayes met the chaplain of the Royal Chapel of the Savoy, who invited a representative from Buckingham Palace to hear one of Roland’s performances. When he sang an unaccompanied rendition of the spiritual “Were You There?”, several of the listeners began to weep. In fact, René Vautier, a French film director, sculpted a bust of Roland with his eyes shut, from a photo taken during this performance. He soon was called upon to give a command performance for the king and queen of England, which led to his associations with Lady Astor, the composer Sir Edward Elgar, and the soprano, Nellie Melba. Hayes was quickly becoming a sensation among the elite. Nellie Melba was ecstatic when she heard Hayes sing “Una furtiva lagrima” from Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore.

Roland continued to study, taking lessons from Amanda Aldridge, a pupil of the legendary Jenny Lind, and who was the daughter of the Shakespearean actor, Ira Aldridge. Roland also began studying with George Henschel, a pupil of Brahms, and the founder and first conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

In Paris, Roland Hayes sang for the rich and famous of Parisian society. He was hosted by, and had the patronage of the Rothschilds, princesses, dukes, duchesses, countesses and baronesses. And he was coached by Gabriel Fauré on the composer’s songs. In Vienna, Roland was coached in the Viennese tradition by Theodore Lierhammer. One Viennese reviewer wrote: “No German could sing Schubert with more serious or unselfish surrender.” Another one wrote: “Do not imagine that it is sufficient to be white to become an artist. Try first to sing as well as this black man did.” This led Roland to write: “I am persuaded that the spirit’s choice of my body to inhabit, has some specific purpose. I am Black for some high purpose in the mind of the spirit. I must work that purpose out.”

In 1923, Roland’s mother Fannie died. His mother had repeatedly insisted that he sing with clearly intelligible diction and enunciation. And just in case it wasn’t perfect, he had the lyrics to each song printed in the concert program booklets. Among the last things she wrote to her son was: “Don’t sing yourself out. Stay in bound of reason and don’t let the folks cheer you to death.” Her last words to him were: “Remember this, you are a continuation of my desire. I have always prayed the good Lord that I might do something good through some of my children. Now you go on, remember who you are and reference your heritage.” Roland was unable to attend her funeral, but he requested that his recording of Sit Down be played at the service. As Hayes’s biographer, Dr. Christopher A. Brooks, wrote: “It was Fannie, after all, who had taught the song to her son. Knowing of his mother’s enslaved background, combined with her personal sacrifices, struggles, and losses, Roland saw the repeated phrases throughout the spiritual, ‘Sit down and rest a little while’, as a metaphor for her life. The final phrase, ‘Oh Hallelujah, in my kingdom’ was an equally meaningful metaphor for Fannie Hayes’s death.”

Roland returned to Boston near the end of 1923, and became the first African American soloist to appear with a major American orchestra in 3 performances with the Boston Symphony conducted by Pierre Monteux. Hayes now had professional management. He began traveling with a personal assistant, and in the 1920’s was earning 6 figures a year.

Not long after the death of his mother, Roland met Countess Bertha Colloredo-Mansfeld in Prague. Starting in 1924, Hayes and the countess began exchanging increasingly passionate letters. She was married with four sons, but fell hopelessly in love with Roland. He wrote: “In preparation for my visits, she would assemble a bibliography of whatever composer we had nominated for studying. She would present me with shelves of books and stacks of music to research and study. I found it so exciting to spend long weeks working together. We read the definitive biographies, and sang and played the music in chronological sequence. We read Goethe, Schiller, and Bismarck for background. In such a way, year after year, we went through Bach, Handel and Mozart, Schubert and Schumann, Beethoven, Brahms and Hugo Wolf, and then the early Italian masters, such as Caccini, Peri, Monteverdi, Lulli, Galuppi, and others.” For 6 years she guided him through the study of composers’ lives and their music. And she accompanied him at the piano as they studied. In letters to the countess, he called her “my revealer of wonders, my guiding star, my divine, my comfort. Oh! What bliss as we work side by side. My being cries out for the safe pillow of your presence.”

About the countess, Dr. Brooks wrote: “She believed he was a genius and the representation of the very best of the Black race. For her, having a child with the tenor meant bringing about the blending of the two races, which would enhance, and perhaps save, humanity.” And in fact, they did have a child, a daughter named Maya, who had 6 children of her own.

In 1924 Roland made his Berlin debut at the Beethoven Hall. Ads for the upcoming concert were placed in German newspapers featuring his photo, announcing that he would be singing songs of Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Strauss and Wolf. The Berliners could only associate Black musicians with jazz, and letters to newspaper editors were published denouncing the upcoming performance as a sacrilege. One newspaper called the event scandalous, and stated that the best Hayes could do would be to remind them of the cotton fields of Georgia.”

The 1,000 seat Beethoven Hall was sold out, and when Hayes came out on stage, people began to boo and hiss at him. He believed that the demonstration was caused by the Nazi Party. Roland stood there with his eyes closed for several minutes, and then offered this prayer: “God, please blot out Roland Hayes so that the people will see only Thee.” Eventually there was silence. Then Roland and Lawrence Brown performed Schubert’s song, Du bist die Ruh (You are Repose/Peace). When they finished, the audience leapt to their feet, cheering and stomping! Singing the music of their beloved Schubert, Roland put the snobbish Germans in their place.

Hayes wrote: “The critical world may have found me perplexing, but said that I had a new kind of vocal instrument, with its own individual color. It meant so much to me to read that I had made the spirituals sound ‘almost as though they have been written by a great master.’” Hearing Roland Hayes sing the spiritual Swing Low Sweet Chariot is a perfect illustration of this. The chariot is a heavenly vehicle to transport people to their home in heaven. But its coded message is a metaphor for abolitionists to come to the South and bring enslaved people home to freedom in the North or to Africa.

In 1948, Roland’s book of spirituals was published. Its original title was My Songs: Aframerican Religious Folk Songs Arranged and Interpreted by Roland Hayes. In 2001, it was republished as My Favorite Spirituals: 30 Songs for Voice and Piano Arranged and Interpreted by Roland Hayes. In contains the sheet music to Haye’s arrangements of 30 spirituals, and Roland’s essays on each of them. Dr. Brooks wrote: “He used the term Aframerican in the forward because he saw the term Negro as a misnomer and believed that Aframerican better reflected those Africans transplanted to the United States.” Hayes wrote about his experience with spirituals as a boy: “It became my duty in the church to learn new songs and teach them to the congregation. It was in this oral fashion that the spirituals were handed down amongst Negroes everywhere, and thus they have traveled all over the South.

“The slave composers were moved by the same fiery spirit that inspired Bach and Schubert. It is their rare combination of art and spirituality that makes for great music. They approached their God humbly. Even in their music they did not dare to speak to him directly. They spoke to him in quiet melodies adorned with hundreds of delicate little turns which were a part of their instinctive modesty in the presence of the divine spirit they venerated. In such a way they asked for deliverance from their sufferings and peace at the last.”

In 1926, Roland traveled back to his ancestral home in Georgia, where his mother had been enslaved. There he met with the elderly Joe Mann, the former owner of his ancestors, who was now poverty– stricken and in failing health. Roland informed the old man that he had purchased the 600 acres of land where his mother, her immediate family, and her ancestors had once been held in bondage, and welcomed Mann and his sickly wife to stay on his land as non-paying residents. The son of the once enslaved mother would become the master of her former captor. However, before Roland could formally take possession of the land, Joe Mann and his wife died.

Hayes envisioned the property not only as a functioning farm, but as an artists’ colony. He had a friend create an architectural design that included dormitories, classrooms, a museum, a small hospital, a performing venue, and an elaborate garden for reflection and solitude. He also asked an architect to design a school and an Egyptian–style building to be dedicated to the memory of his mother. Hayes wrote: “I wanted to invite promising Negro boys and girls, painters and poets and musicians to my farm in Georgia, where they could be tested for vocation: exposed to the arts in native and imported forms, and trained in the direction of their several propensities. I thought of making my house in Boston a kind of hostel to which boys and girls from the South could go for their intermediate education. After that, my villa in France was to have been open to the cream of the crop, those young people whose early promise had begun to be realized in Boston.” And he invited the preeminent African American scientist and inventor, George Washington Carver, to visit the farm. Carver responded that Hayes was doing God’s work for humanity: “What you are doing, my beloved friend, is bigger than one race. It is a contribution to all mankind. My prayers will follow you all the way wherever you go.” And he signed it: “Yours with genuine love and admiration, G.W. Carver”. Unfortunately, after the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression, Hayes was forced to abandon these plans.

In 1932, Roland married his 1st cousin, Alzada. They had a girl, named Afrika, who eventually had two daughters of her own. Once they were married, Roland abruptly ended his relationship in Europe with the countess and their daughter, Maya.

In 1938, Roland invited a white Canadian student to come to his farm in Georgia to study voice with him. Soon, white locals made threats against Roland and the boy who was staying in the same living quarters with the Hayes family, because they were violating the norms of the separation of blacks and whites. Roland conceded to local segregation customs, and sent the young man away. In 1947, Roland sold the farm in Georgia, and bought one in Massachusetts. The experience, however, did not dissuade him from his goal of bringing the races closer together.

“We all have the same divine spark, whether our skin is white or black or yellow or brown. I want to show that in my singing. Real art that goes to people’s hearts leads to my life’s goal: the end of race hatred, with no difference between the colors of the skin. Peace and brotherhood all over the world.”

Touring was often very hard on Hayes. In 1942 he wrote: “I had nearly always been required to pay as indeed I still do at least 50% more than white artists are charged for hotel accommodations and services. In American cities which I’ve visited for the first time, I often found the audiences inquisitive or skeptical, or even hostile. My managers tried to spare me discomfort and humiliation by making travel arrangements for me well in advance, but even so, hotel keepers now and again refused to put me up when the day of my arrival actually rolled around. Once when I was interviewed while I was dining alone in my room in a Duluth, MN hotel, I was asked whether I had been requested to stay out of the public dining room. I admitted that I had been so ordered. Stones have been thrown through the windows of my house in Brookline. I have been refused a bed in a hotel in Tucson, a chair in a Seattle lobby, a meal in a restaurant in Duluth, and once not so long ago, I was beaten and thrown into jail.”

By 1942, Hayes had long been one of the most beloved, successful and highest paid classical performers of his time. Yet, that summer, Roland’s wife and daughter had been verbally abused and kicked out of a shoe store in Rome, Georgia. When he confronted the owner of the store, police were called and threw Hayes into the back of a police car, where they brutally beat him so badly that his lip was cut, his jaw was bruised and his eyes were swollen shut. They then locked up Roland and his wife in a prison cell. The incident was widely written about, including in the NY Times, and Time magazine. Lawyers from around the country offered their services pro bono to sue the guilty police. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt spoke out about the incident. The people of Rome, GA were shamed by the negative national and international attention. Roland Hayes’s autobiography was published two months after the incident. It is entitled Angel Mo’ and Her Son, Roland Hayes. “Angel Mo’” is short for Angel Mother.

Here is an excerpt from an essay entitled My America that the great Harlem Renaissance poet, Langston Hughes published a few months after the incident: “America is the land of where the best of all democracies has been achieved for some people, but in Georgia, Roland Hayes, the world famous singer, is beaten for being colored and nobody is jailed, nor can Mr. Hayes vote in the state where he was born. Yet America is a country where Roland Hayes can come from a log cabin to wealth and fame, in spite of the segment that still wishes to maltreat him physically and spiritually, famous though he is.”

Dr. Brooks wrote about “the very savvy and shrewd businessman that Roland was, a man who, with the equivalent of a high school diploma, could negotiate very complex contracts and was on top of every aspect of his career.” Yet, Hayes isn’t well known at all today. Why not? He himself is partially to blame. Once, after making some recordings for a record company, when unable to agree on the terms of distribution, he destroyed the master discs, so that the recordings could never be published. He was opposed to the then–new medium of radio, refusing to broadcast his singing because he felt that his art was not intended for mass distribution through radio. And when Hayes was invited to perform at the White House for First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the idea was for him to be paired on a program with a jazz singer to demonstrate the musical versatility of African-Americans. Hayes refused because he didn’t approve of jazz, and considered this sharing of the program to be below his artistic standards!

Roland Hayes’s last performance was in 1973 as a fund raiser for the Longy School of Music in Cambridge, MA. He was 86! In his last years, Hayes displayed the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, and died in 1977 at 89 from a respiratory complication. His archives comprising more than 75,000 documents are housed at the Detroit Public Library, which established the Roland Hayes Trail Blazers Award to honor African American artists whose careers mirror his high artistic goals.

A museum in his honor was established in his home town of Calhoun, Georgia. A school in Chattanooga, Tennessee bears his name, as does a grade school in Saint Alban, West Virginia. The French government awarded him the Palmes Officières d’Académie for his service to French music. He was inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame. The Roland W. Hayes Concert Hall is at the Chattanooga campus of the University of Tennessee. A documentary, The Musical Legacy of Roland Hayes was made in 1990. He was the recipient of the NAACP’s Spingarn Award, and is the recipient of 8 honorary doctorate degrees.

A museum in his honor was established in his hometown of Calhoun, Georgia. A school in Chattanooga, Tennessee bears his name, as does a grade school in Saint Alban, West Virginia. The French government awarded him the Palmes Officier d’Academie for his service to French music. He was inducted into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame. The Roland W. Hayes Concert Hall is at the Chattanooga campus of the Univ. of Tennessee. A documentary, The Musical Legacy of Roland Hayes was made in 1990. He was the recipient of the NAACP’s Spingarn Award, and is the recipient of 8 honorary doctorate degrees.

Several years ago Roland’s American and European families finally met! Through his 2 families he left behind 2 daughters, 8 grand children and many great grand children. His great grandson, Wenceslaus Bogdanoff is a bass singer.