Q: “When did you realize you wanted to become a conductor?”

CC: “When I was 17 years old—at my first job as assistant conductor at the Usdan Center which had four youth orchestras. I remember the sensation I felt the first time I stepped onto the podium to conduct. I knew immediately that I was home.

“My piano teachers wanted me to concentrate on learning piano repertoire, and I decisively fought them because I wasn’t interested in becoming another piano virtuoso. I wanted to learn ALL the repertoire: lieder, chamber music, symphonies, operas—I wanted to become really good at sight reading scores at the piano. I felt I was like a giant sponge. There was this huge universe of music, and I was eager to start taking it in.”

Q: “What is the single most difficult aspect of your profession?”

CC: “It’s being flexible. Music making is never the same. It’s always changing, and always at the last moment. It’s crucial not to get blown off center when your expectations are destroyed. That’s one thing about life: It’s always changing; it’s never stagnant. And it’s important to recognize that and be ready to adapt to whatever happens as it’s unfolding. How we choose to react is what determines the outcome.”

Q: “Who are your greatest influences?”

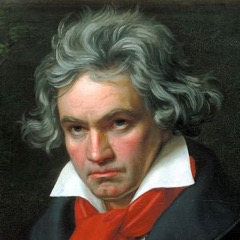

CC: “I’d have to say Beethoven—for his great spirit of perseverance despite his evolving deafness. He could have given into despair and become a hopeless alcoholic like his father. Speaking of fathers…my Dad. I watched him very carefully. He had an incredible ability to remain most calm during times of great stress and upheaval all around him. He accomplished seemingly impossible tasks in what he called his ‘own quiet way, without any fanfare’. And he had a heart of gold. People felt his heart, and reacted in kind.

“As for conductors, certainly Toscanini. To start with, his standards and ideals were so incredibly high. He was a perfectionist, and his results were outstanding. That’s a wonderful measuring stick to have.”

Q: “Is it still necessary for American artists to establish themselves in Europe before gaining a strong foothold in the U.S.?”

CC: “That’s a good question. Yes and no. For example, two of the most successful American conductors, James Conlon and Michael Tilson Thomas both spent decades conducting abroad before having music directorships here in the U.S.

“Some of the biggest orchestras such as Los Angeles, Chicago, Cleveland, Boston and Philadelphia still have foreign born music directors, and interestingly, there are a lot of Americans working in Germany—conductors and singers. When I tour Russia, there is always considerable media coverage because I’m a foreigner, and an American at that.

“The scenario is slowly changing though, because there are now American music directors in several U.S. cities. The notion of: ‘That which is imported must be superior to that which is domestic’ is starting to fade.”

Q: “Your choice of repertoire often emphasizes large 19th century romantic compositions. Why is it that you conduct neither very much 20th century nor contemporary music?”

CC: “Orchestra boards and managements are very careful about programming. And conductors too, are sensitive to the receptivity of their audiences. It’s a question of education. There’s no reason why audiences anywhere can’t be introduced to new music, and fully enjoy it.

“From the 20th century I’m particularly attracted to the music of Ives, Bartok, Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Strauss and the contemporary Latvian composer, Peteris Vasks. I believe their music will survive and be part of the standard repertoire 200 years from now.

“Although I’ve conducted lots of world premieres and first readings, my priorities have been to embrace the great monuments of Western music—Beethoven’s 9th, his Missa Solemnis, Verdi’s Otello, Wagner’s Ring cycle, etc. This doesn’t cancel the responsibility to perform new music, but its success is heightened if we create the best timing and conditions for its presentation.”

Q: “Why are so many orchestras not able to gain enough support to stay healthily afloat?”

CC: “Patrons of the arts have traditionally saved countless numbers of arts organizations in this country time and time again. It’s a matter of education. If during the first 12 years of school, students do not receive instruction in music appreciation, in singing and/or playing in school ensembles or choirs, are not brought to concerts, opera or ballet, if arts organizations don’t come to the schools regularly to share their art with the students, then it would be foolish to expect these students to be part of the classical audience when they become adults. It’s up to us. It’s everyone’s responsibility to share great art with young students. We have to undergo a huge paradigm shift when it comes to arts education, and not rely on nor expect schools to provide music instruction, nor should we should expect our government to subsidize the arts. Sure, in Europe, governments have supported cultural institutions historically, but this is not Europe. I’m certainly not opposed to government subsidy of the arts, but the reality of the U.S.–irrespective of which party is in office at any given time, or whether taxes are raised or lowered—is that there’s no reason why the arts shouldn’t be available to everyone. And it will happen. Many people realize that it’s wrong to just depend on a handful of angels to support one’s arts organization. There are lots of very wealthy individuals who have established trusts and foundations to give away money, and there are huge global corporations that have accumulated incredible piles of cash.”

Q: “Our audiences are not getting younger. Will there eventually be a box office crisis as audiences age and are not replaced by successive generations?”

CC: “Gary Graffman gave an interesting talk at the 2002 annual conference of the American Symphony Orchestra League, in which he stated that in his youth, audiences were mostly grey haired, and continue to be so today, 50 years later!

“I recently attended a performance in New York City’s Central Park, and was delighted to find a relatively young crowd there. Those with grey hair were certainly in the minority.

“It’s not as bleak as it sometimes may seem. For example, there are opera companies all over the U.S. that certainly didn’t exist 30 years ago. There’s a great profusion of summer music festivals in the mountains, in the desert. You now can purchase recordings of the complete works of many composers, which is something you couldn’t do even 20 years ago. There are now videos and DVDs of every opera that is performed today. It’s become quite common to create music on a home computer or even a laptop with virtual recording studio software to be had for hundreds of dollars replacing equipment worth tens of thousands of dollars, making digital music more accessible and easier to compose. Many public libraries have recordings of much of the standard repertoire, and a lot of the more esoteric repertoire. So it’s hard to generalize and say: ‘Everything points downward’, because these very positive developments are part of the current overall reality.”

Q: “What are your preferences with regards to orchestral sonority and color? Are there particular orchestras whose style is closer to your ideal sound than others?”

CC: “This may surprise you, but I celebrate the sounds and colors and styles that differentiate certain orchestras and regions from one another. One can truly marvel at the ability of some of the American and English orchestras to practically sight read anything. In one way, as orchestral standards have continually grown higher and higher over that last 100 years, there has been a tendency toward an overall unified homogenized sound. But there’s still something very unique about a Russian orchestra playing Tchaikovsky. It’s definitely a certain sonority that can’t be matched anywhere. It’s an extraordinary, spiritual experience to conduct Russian music with Russian orchestras for Russian audiences. By the same token, I’ll never forget the first time I heard the Vienna Philharmonic play the 1st movement of Beethoven’s Pastorale Symphony—Now THAT’S a unique individualized sound!

“What is sonority? It’s an expression of the players’ hearts. It’s very subjective.

“There’s no superior color or style. Historically, conductors were legendary for creating certain styles of sound. Stokowski was an organist—and was highly interested in color. He’d even ask woodwind players to change reeds to get a different color. Toscanini and Ormandy were string players, and this was a key to their sound. Toscanini, initially a cellist, was constantly admonishing orchestra players to sing on their instruments, while vibrating over his heart on an imaginary cello fingerboard. Orchestras once played with portamento. That is now considered taboo—but in the ‘20’s and early ‘30’s it was quite common, and extraordinarily beautiful.”

Q: “This brings us to the original instruments concept. Do you utilize original instruments and specialist players in your performances of 17th and 18th century music?”

CC: “Certainly composers such as Bach and Mozart and Beethoven were constantly seeking out and celebrating new, improved, superior instruments that were increasingly stronger and more versatile. This evolution in the development of instruments has continued to the present day. And I see no reason to limit the vast, dramatic improvements that continue to be made, just because these composers’ lives happen to have ended!

“Certain aspects of articulation and bowing were influenced by the design and limitations of old instruments. It’s a hard call to make: When do we heed the articulation demanded by the instruments of a certain period vis à vis what is inherently found in the music itself?

“Leonardo da Vinci designed a fascinating instrument which combined the sonority of string instruments (through the use of bow hair touching strings), with the agility advantages of a keyboard, with the seamless sustaining power of an organ through a foot pedal, which caused a wheel of bow hair to turn! In Barber’s Adagio for Strings where one wants this very long lyrical line to be unbroken—the last thing you’d want to be aware of is a uniform changing of bow direction by a string section. Here, this instrument of da Vinci’s would be ideal for the task. In this composition I insist the musicians use free bowing to maintain an unbroken line.

“Clearly there are advantages to utilizing certain performance practices from each period. At the same time I’m convinced that composers of the past would be ecstatic upon encountering the sound and capabilities of the incredible modern instruments being built today. The wisest outlook is to keep a very open mind. And more important than which instrument or what articulation is being used—is whether the performers are really playing from their hearts. Are they excited about the music? And is the audience thrilled, excited, saddened and moved?”