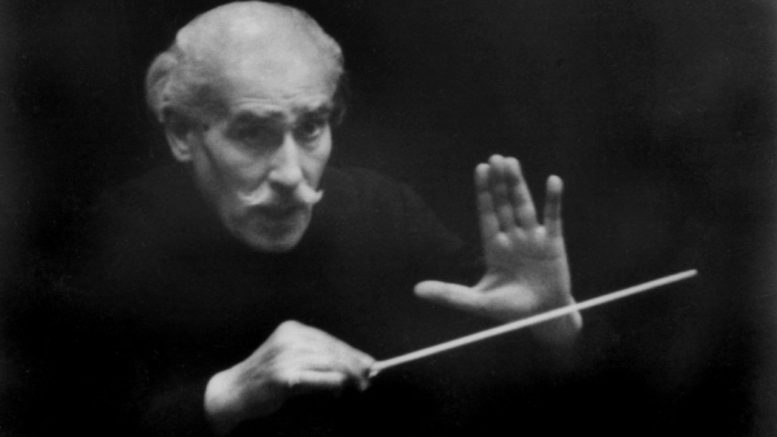

Toscanini was born in Parma in 1867. His career spanned an incredible 69 years. Beginning in 1898 he was the artistic director of La Scala for several years, from 1908-1915 the principal conductor of the Metropolitan Opera, the artistic director of La Scala during the 1920s, music director of the New York Philharmonic in the ’20s and ’30s, and for 17 years the principal conductor of the NBC Symphony. He conducted the world premieres of Barber’s Adagio for Strings, I Pagliacci, La Boheme, The Girl of the Golden West, Turandot, the American premieres of Boris Godunov, and Ravel’s Bolero, and the Italian premieres of Salome and Pelleas et Melisande. Toscanini had a photographic memory. He performed and rehearsed over 600 compositions from memory. He died in 1957 in New York at the age of almost 90.

When I was a teenager I interviewed 50 of the artists who knew and worked with Toscanini, and broadcast these interviews on a radio show I produced called The Toscanini Legacy. That’s me at the radio station, and yes, that is all my own hair! The musicians were in their 70s and 80s when I interviewed them, and were quite young when they worked with Toscanini, who in those years was in HIS 70’s and 80’s. These interviews with the musicians are a direct link to the 19th century. I was struck by the vividness of their recollections and the enthusiasm with which they recalled events they had participated in thirty to forty years before.

Toscanini recalled: “The first impression I received of Wagner’s music goes back to 1878 when I was 11 and heard the Tannhäuser Overture at a concert in Parma and I was bewildered.”

In 1884, while a student at Parma’s Royal Conservatory of Music, the 17 year-old Toscanini played cello in a production of Lohengrin at Parma’s Teatro Regio, and was so moved that he wept. He wrote: “It was then that I first acquired a great, marvelous awareness of Wagner’s genius. From the first rehearsal, or rather from the first bars of the Prelude, I was overwhelmed by magical, supernatural feelings; the celestial harmonies revealed a new world to me, a world whose existence no one had even the slightest intuition until Wagner’s transcendent spirit discovered it.”

The conservatory’s director, Giusto Dacci believed that Mendelssohn had reached the limits of harmonic expression, and the students were discouraged from studying Wagner. Therefore the young Toscanini secretly studied whatever music of Wagner he was able to find.

He wrote about the Prelude to Lohengrin: “…When Wagner set down this simple A major chord for the Violins and Woodwinds, I’ve always imagined that at a moment of great, sublime inspiration he disappeared from the earth, went up to heaven for a time, and came back down bringing that magical chord, of whose existence no one before him had dreamt…”

In 1888, at age 21, Toscanini was in Bologna listening to the first performance in Italy of Tristan und Isolde. By the end of the second act he decided to abandon his ambition to be a composer, even though several of his compositions had already been published.

In 1895 Toscanini began his first artistic directorship: in Turin. He opened the season with Götterdämmerung, sung in Italian, as all operas were at that time in Italy. Amazingly it had a run of 22 performances!

Toscanini’s first rehearsal at the Metropolitan Opera was in 1908 with Götterdämmerung, which he led from memory. Amazingly, he heard and corrected mistakes in the orchestra parts, which for decades, none of the well-known German conductors had noticed. In 1926 Toscanini conducted the New York Philharmonic for the first time, and he included Siegfried’s Death and Funeral Music from Gotterdammerung. For his last appearance with the New York Philharmonic Toscanini included Siegfried’s Death and Funeral Music.

1932 he wrote: “Among operas, I value those of Wagner and Verdi above all. It is difficult to state a preference for one of Wagner’s operas. I have noticed that if I am conducting one or another of Wagner’s operas, or playing it at the piano, whichever one it happens to be takes possession of my heart. And yet, every time I glance at the score of Parsifal, I say to myself: This is the sublime one.”

The timing of Parsifal conducted by Toscanini is by far the slowest ever recorded in Bayreuth’s archives going all the way back to its first production in 1882!

Alan Shulman remembered: “At a dress rehearsal of an all Wagner program. We did the prelude to Parsifal. When we finished he said, ‘Thank you, see you at the concert tonight.’ And my stand partner and I sat there three or four minutes. We were so moved by the magnificence of the man’s concept, that we just couldn’t pack our instruments away, and head for home, and rest before the concert. It was an incredible experience.”

The Viennese photographer Robert Hupka took over 1,500 photographs of Toscanini at rehearsals and recording sessions. Hupka was very excited about the publication of my book, The Real Toscanini: Musicians Reveal the Maestro, because it is based on 50 interviews I recorded with musicians who knew and worked with the maestro.

Fred Zimmermann, who played bass with Toscanini said: “Wagner with him was deeply stirring, deeply spiritual; and being part of it was a transcendent experience. After the concert I just couldn’t bear to go into the subway; and so I walked for blocks and blocks to my home with the sounds of the performance ringing in my mind.

Toscanini conducted the first ever symphony concert on TV in 1948. For this historic occasion he chose an all-Wagner program and he conducted a second televised all-Wagner concert in 1951.

Toscanini conducted the Forest Murmers from Siegfried on both of his televised all-Wagner concerts. He conducted more performances of Die Meistersinger than any other Wagner opera. And the three works he conducted the most frequently in symphonic concerts were Debussy’s La Mer, Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, and the Prelude to Act I of Die Meistersinger.

Hugo Burghauser, the chairman of the Vienna Philharmonic in the 30s recalled Toscanini conducting Die Meistersinger at the Salzburg Festivals in 1936 and ’37. “I had heard Die Meistersinger for 25 years; but this second act was an entirely new experience for me. In sound and dynamics, in clarity, in expression–this was the ultimate. And afterwards, when we ran up to Toscanini’s dressing room, I never saw him as he was then. He said: ‘Com’un sogno. Like a dream.’

20 years later, somebody played for him a recording made from the broadcast of one of his Meistersinger performances in Salzburg. When he heard the second act he was touched…and said: ‘It’s a heavenly dream.’ He was moved to tears– such was the power of his own conducting. And of course for all of us also.”

Marcia Davenport, a writer and friend of Toscanini recalled: “We who heard that rehearsal and saw it…were overwhelmed with emotion. But when the curtain fell on the finale, and then went up again as curtains do at rehearsals…there stood the entire company on stage, every one of them in tears. The Maestro himself stood motionless in his place with his right hand covering his eyes.”

Lotte Lehmann who sang Eva in 1936 recalled the effect Toscanini had on the baritone singing Hans Sachs: Hermann Nissen. According to Lehmann, Nissen had a calm personality and was not easily carried away by emotion. “Even this man was stirred to his very depths by the great Maestro. I can still see him, his eyes overflowing with tears, as he turned around after the ‘Wach auf’ chorus in the general rehearsal saying, ‘My God, how shall I be able to sing now? This damned demon down there has absolutely devastated me with his fire.'”

After the first performance Toscanini wrote: ” I was in a daze for two days! I was dead tired. It was a moving performance. I don’t think I’ve ever obtained a better performance of Meistersinger. Can you imagine that the singers were crying at the end of the opera? Bruno Walter came back after the 2nd act; he told me that we had brought off a miracle! I’m so happy to tell you this…But I was quite frightened…”

And after the second performance he wrote: “Yesterday evening, after Die Meistersinger…I was exhausted…as if I’d done battle against forces greater than my own…When I’m working I don’t have time to feel joy; on the contrary, I suffer without interruption, and I feel that I’m going through all the pain and suffering of a woman giving birth…”

Toscanini conducted Die Meistersinger again at Salzburg the following summer with Maria Reining as Eva. Late at night, after the first performance he wrote: “After the first act, Eva Chamberlain (Wagner’s second daughter) came with tears in her eyes and said to me, “‘My dear friend, I feel as if I were hearing Die Meistersinger for the first time. Never, not even in Bayreuth’s early days, has it made so great an impression as this evening.’ And she kissed my hands, bathing them with her tears, which seemed unending… I foresee and predict a sleepless night. My nerves are still tense; as I write, I have to stop every once in a while, because my hand jerks, as if from epilepsy…”

In 1898 Toscanini chose Die Meistersinger to begin his tenure as artistic director of La Scala. The last performance Toscanini conducted at La Scala was an all-Wagner concert. And his last performance ever was in Carnegie Hall with an all-Wagner program.

In 1899 Toscanini visited Bayreuth. He sent his brother-in-law, a postcard of Wagner’s grave, and wrote: “Here is the tomb of the greatest composer of the century.”

Siegfried Wagner, the composer’s son, was astounded when he heard Toscanini conduct Tristan und Isolde at La Scala in 1901 and wanted to invite him to conduct at Bayreuth but was met with strong opposition to engaging a non-German-school conductor. Siegfried told Toscanini that the production excelled even those of Munich and Berlin, and reported to his mother, Cosima Wagner, about the excellence of the production. She wrote the maestro a letter of gratitude.

Toscanini had presided over the installation of what was then the most modern stage lighting system in Europe, and German theatre managers all sent representatives to observe it.

In 1930 Siegfried Wagner finally succeeded in bringing Toscanini to Bayreuth where he conducted five performances of Tannhäuser and three performances of Tristan und Isolde both staged by Siegfried. Toscanini returned to Bayreuth in 1931 and conducted five performances of Tannhäuser and five performances of Parsifal. He was the first non-German-school conductor to perform at Bayreuth, which the maestro considered to be a great shrine of art and therefore refused any compensation.

The violist, Nicholas Moldavan, remembered that the musicians had resented the intrusion of an Italian in this shrine of German art until Toscanini’s first rehearsal of the orchestra, when he reduced them to stunned silence. Conducting as always, from memory, he detected in their playing mistake after mistake in the orchestral parts that had gone undetected for half a century by the German conductors. At a rehearsal of Tristan, Toscanini asked why no one was playing the cymbal part at the end of Act I. He was told that there were no cymbal notes in the parts. The maestro insisted that the manuscript be consulted, where, to the Germans’ surprise the cymbal notes were found, clearly notated! Lauritz Melchior who sang Tristan and Tannhauser that summer, recalled Toscanini saying: “What Wagner meant is very clear. Just examine the score. You will find everything there.”

Alexander Kipnis, who sang the role of King Marke recalled: “He objected to the fact that the singers gave more importance and emphasis to pronouncing the word than to singing the music…

The chief characteristic of Toscanini’s Tristan was its lyricism, which the typical German conductor doesn’t bring to the work…I always loved the lyrical approach to Tristan, which I heard many times from other conductors, but never in such a degree as from Toscanini. I would say his Tristan was like an Italian opera; and curiously enough, some time before Toscanini came to Bayreuth, Siegfried Wagner said Tristan should be sung like an Italian opera…That’s the way Tristan should be sung, because it was not a Teutonic opera.”

Ernest Newman, born in 1868, was the leading British music critic of his generation and the author of more than ten books on Wagner. Hearing Toscanini conduct Tristan at Bayreuth he wrote: “I thought I knew that work from end to end and from outside to inside; but I was amazed to find, here and there, a passage coming on me as a new revelation and going through me like a dagger stroke…The total effect was indescribable: I shall remember it and thrill to it to my dying day…”

In 1930, Toscanini’s first summer at Bayreuth, he also conducted a new production of Tannhauser. Melchior remembered that the first rehearsal had taken place while Siegfried was hospitalized, and that Toscanini wept through it. Siegfried suffered a heart attack and died during the 1930 festival.

Kipnis recalled the concert in the Festspielhaus a few days after the burial. “On the program was the Siegfried-Idyll conducted by Toscanini: it was the most beautiful I have ever heard in my life; and everyone in the audience had tears in his eyes from the sound of this music. Toscanini’s Tannhäuser was different. His approach to every phrase was very soft…It was lyrical.”

Daniela Thode was Cosima Wagner’s daughter with Hans von Bülow. She and her half brother, Siegfried planned a gradual light change from the Venusberg to the Wartburg In Tannhäuser. Toscanini insisted that the composer’s instructions for a sudden light change be followed. And in a letter to her he quoted Wagner’s words: “The great transformation scene takes place all at once…the valley bathed in midday sunlight at its brightest.”

The cellist and conductor Alfred Wallenstein remembered: “During a rehearsal of Tannhäuser, when Elizabeth entered for Dich, teure Halle, the stage was darkened. Maestro stopped and asked: ‘Why is the stage so dark?’ And Siegfried Wagner said: ‘That’s what Father wanted.’ And Maestro said: ‘Father wanted?! You have the writings of Father?’ They had, of course at Villa Wahnfried…so they went straight into the library, and he took down the particular volume he wanted, turned to the exact page and said: ‘Here! Read!’ And Wagner [wrote] that for Elizabeth’s entrance there should be the brightest lights possible.”

Toscanini returned to conduct the following year at the 1931 Bayreuth Festival. He was the favorite of the Wagner family. There was no Bayreuth festival in 1932. In 1933, Toscanini agreed to conduct five performances of Parsifal and eight of Die Meistersinger. However at the end of January 1933, Hitler became chancellor and immediately began destroying democracy in Germany. Toscanini was greatly alarmed and on April 1st sent a telegram to Hitler protesting the boycott of Jewish musicians and the dictator’s racist policy. This was published on the front page of the NY Times.

Two days later Hitler wrote to Toscanini, inviting him to Bayreuth that summer and expressing how much he was looking forward to personally greeting him. Toscanini responded indicating that this was not likely to happen, and a month later he informed the Wagner family that he would not be returning to Bayreuth. Several years later he referred to giving up Bayreuth as the deepest sorrow of his life.

Siegfried’s daughter, Friedelind Wagner, was strongly influenced by Toscanini’s anti-Fascist and antiracist attitudes and soon became an anti-Nazi renegade in her family. During World War II, Toscanini helped her immigrate to the United States and supported her for a long time. She considered herself to be an honorary stepdaughter of Toscanini and said: “I have yet to meet a great artist whose character is as wonderful as his artistry–except when his name is Toscanini.”

In 1936 and ’37 the maestro traveled to Tel-Aviv and trained and conducted the first concerts of a special orchestra comprised of Jewish refugee musicians escaping Nazi persecution. When he returned in 1938, he insisted on conducting the 2 Lohengrin Preludes. This orchestra is now known as the Israel Philharmonic.

My mentor, the Buddhist philosopher, Daisaku Ikeda wrote:”Toscanini was not able to separate art from daily life. For him, pretending not to see injustice was not only stifling to his humanity but fatal to his art. As he said: ‘When one’s spirit is twisted, one’s backbone is twisted as well.’ It was Toscanini’s solid conviction that his daily actions must reflect his conscience.”