by Moshe Denburg

What is Jewish Music? – One Jewish Musician’s Take

Over the years, in presenting workshops on the topic, I began with the question: What is Jewish Music? Answers to the question varied widely – some said it was happy-sad, undoubtedly referring to typical Jewish songs. Others responded that it is music related to life passage events. Yet others to specific Jewish languages, such as Yiddish or Hebrew. Many even considered music Jewish if it was written by a Jew. According to this rule, White Christmas counts as Jewish Music because it was written by Irving Berlin, a Jewish immigrant to the USA!

I would like to start this discussion by giving my take. Jewish Music, whether now or in the past, is that which is related to Jewish religious experience. I mean by this that at some point in the past, near or distant, Jewish experience and identity was a religious and ritualistic one.

Take Klezmer for example. In its manifestation as an instrumental form, with many correlations with the music of non-Jewish cultures, it is still very identifiably Jewish; and, I would assert, this is mainly because it has become associated with Jewish life passage events and communal celebrations. And not coincidentally, its main modes are the same as those traditionally utilized by the Cantor, in leading prayers in the synagogue. I will explain the term mode soon enough, but for now, take the term to be synonymous with melody. So, somewhere along the line, a piece of music deemed Jewish related to the ritual Jewish experience, the religious/ritual context.

This said, I am perfectly willing, and in fact wish to admit, that what began in ritual practice and prayer has gone very far afield – certainly one may utilize prayer modes for life passage events, but then other musical ideas are brought into the mix.

The Idea of Intercultural Synthesis

Jewish people have always lived in a wider world, which includes other cultures not rooted in Judaism, and one may argue that it has always been a Jewish imperative to integrate some aspects of other cultures into Jewish practice. It certainly has been a hallmark of Jewish experience to reach out to other cultures, to honour them, to adapt to them and to contribute to them. Some stuff we integrate into our own practice, whether in the synagogue or in a somewhat more secular sphere, like a wedding reception. The Yiddish Theatre is an example of this celebration of Jewish life, via the integration of many non-ritual musical and poetic ideas. However, in its celebration of lived Jewish experiences, its music is definitely Jewish.

Some Yiddish songs have borrowed rhythms from other cultures, most notably ‘swing’ in America. Swing is, of course, borrowed from jazz, and is an example of how Jewish musicians have borrowed various musical elements from the cultures around them. So this brings us to an idea that is well-accepted by Jewish musicologists. The idea is what I would dub, ‘Intercultural Synthesis’. In other words, due to our constant adapting to the cultures around us, Jewish music is a type of intercultural synthesis.

There is a cultural survival strategy in this. In order not to assimilate completely into cultures not their own, Jews borrow from them and contribute to them, and thus retain a Jewish identity in their art and culture.

Jewish people, who for over 2000 years have been treading water in cultures not their own, might have become inadvertent experts in this adaptation and integration strategy. So, the klezmer (the Eastern European musician) played with non-Jews, and shared a great many musical ideas, borrowing and contributing. This still goes on today, and more and more deliberately I should add. Take American Folk Music for example, which, in contemporary Jewish music plays an important part, folky melodies forming the basis for many songs based on liturgical texts. Jews utilize many secular song forms in their prayers in order to bring people into the synagogue from the secular world outside. This activity is part and parcel of the intercultural synthesis of which I speak.

The 3 streams of Jewish Music – a Historical Atlas of Jewish Music

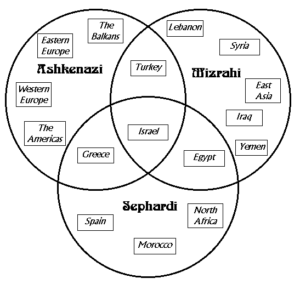

To begin our discussion of the Many Worlds of Jewish Music, it will be helpful to give an overview of Jewish Music. We can describe Jewish Music as having three distinct streams. One is the Ashkenazi, or Western stream. This includes Klezmer, and is music originating in Eastern Europe and extending to the rest of Europe and the Americas.

The second stream is the Sephardi, which refers to Mediterranean cultural sources, including Spain, Portugal, North Africa, Greece, and Turkey.

The third stream is the Mizrahi, literally Eastern, and refers to the music of Jewish people who resided over the centuries amidst Arabic and other Middle-Eastern cultures.

Of course, these three streams are not completely separate but do in fact intersect in many places. Have a look at the following diagram.

The 3 streams of Jewish Music

The music that originated in Eastern Europe (the Balkans, Romania, Bulgaria, among others) and moved westward and northward throughout Europe and later into North America, belongs to the Ashkenazi tradition. It includes Klezmer music. ‘Ashkenazi’ refers to Jews who in the 9th century began to settle along the banks of the Rhine. Since these Jews are the forebears of much of European and Western Jewry, ‘Ashkenazi’ today refers to Jewish people of a Western cultural orientation.

Other than Hebrew, the traditional Ashkenazi language of speech and song is mainly Yiddish; nowadays, English and other local languages have come to play a large role in Jewish Music of the Ashkenazi stream.

By the way, the traditional modes of prayer utilized in Synagogue services, and the modes utilized in Klezmer instrumental repertoire are very much the same. Here’s a quick explanation of the term ‘mode’, and how it differs from the term ‘scale’.

A scale is a collection of notes, whereas a mode is a way of organizing the notes of a scale into melodic combinations. A mode utilizes certain typical melodic formulas for opening and closing a piece, and abides by certain rules governing the emphasis on one or another note or groups of notes. Thus a scale is simply a template from which modes and melodies are made.

Apart from Yiddish, Ashkenazi music – as is the case with all the streams – is steeped in Hebrew, the language of prayer, of the Hebrew Bible – more commonly known as the Torah – and of the land of Israel. And there are also typical rhythms associated with the Ashkenazi stream. One very important one is known as a Freylakh, literally ‘joyful’, and it is essential for the dancing at Jewish celebrations.

The Sephardi stream of Jewish Music refers to music that originated around the Mediterranean, from Spain and North Africa to Turkey and Greece. In Hebrew, ‘Sephardi’ literally means Spanish, and alludes to the fact that until the Spanish expulsion of all non-Christians in 1492, a very fruitful Jewish culture existed in Spain. When these Jewish communities were expelled they migrated to places all around the Mediterranean basin – Morocco, Egypt, Turkey, Greece, etc. They took with them a 15th century version of Spanish which they called Ladino (Judeo-Spanish), and over the centuries it incorporated many Hebrew words, as well as words from the various tongues spoken where these Jews made their homes.

Sadly, much like Yiddish, Ladino is not a spoken language today. But, also like Yiddish, its repertoire has been kept alive and has been given new renditions and arrangements.

The music of Eastern Jews, from the Eastern Mediterranean and eastward into Asia can be designated as the Mizrahi stream of Jewish Music. ‘Mizrahi’ literally means ‘Eastern’. This music is the child of the interaction between Jewish people and the cultures of Arabia, Turkey, and Persia. Generally, this encompasses the following countries: Israel, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, and as far east as India. In song, the main language used is Hebrew, though local languages have also been used, most notably, Arabic.

In Mizrahi music you will hear a very non-Western melodic construction. Eastern modes and melodies utilize ‘in-between’ tones, and may sound out of tune to a western ear at first. But the East is the cradle of the great modal traditions of the world, traditions that go back thousands of years. Yet another typical aspect of Mizrahi music features many notes on a single sung syllable, also known as melisma.

Music for Celebrations and Communal Life – Ashkenazi

The World of Klezmer Bands

Klezmer is a very popular category of music, and in some instances today – in the West – it has become synonymous with Jewish Music itself. Of course, Klezmer is but one branch of the Ashkenazi stream of Jewish Music, an important one for sure, but it is not the entirety of Jewish Music, nor even the entirety of Jewish Music in the Ashkenazi stream.

‘Klezmer’ is a Yiddish word created from two Hebrew words – kley (instruments of), and zemer (song) and it denotes the individual Jewish musician. It has come to denote a band of Jewish musicians, as well as an entire Jewish musical style originating in Eastern Europe in the 19th century. Thus the Jewish Musician is understood to be ‘an instrument of song’, a channel in this world for sacred melody. And klezmorim, a Hebraic plural of klezmer, means ‘Jewish musicians’.

In origin, Klezmer is the instrumental repertoire of Jewish music making utilized for Jewish celebrations; but Klezmer bands today are some of the main exponents of songs in Yiddish, and thus preserve not only an instrumental style of playing, but songs in the beloved Yiddish language.

There is a vast world of Klezmer bands, ranging from those who are dedicated to preserving the original tradition, to those who are very experimental.

As mentioned, traditional Klezmer does not, strictly speaking include Yiddish song, but nowadays most Klezmer bands do include them. The great repository of Yiddish song, traditionally speaking, was the Yiddish Theatre and songs that were composed for performance and recording in Europe and America in the 20th century.

Chassidic Music and Nigunim

A tremendous contribution to Jewish Music is the Hassidic Nigun. A nigun is literally a tune or a melody, and is linked to the Hassidic (Jewish devotional) tradition of seeking simplicity in one’s expression before God. The tradition holds that a nigun is a thread that can bind a human soul to god. Generally the nigun is sung without words, in fact, a wordless Nigun is deemed a more direct vehicle for uniting with the divine than melodies sung with text. Thus, certain syllables are utilized, like Ya bi bi bi bam, or di gi di gi day, and so on.

It is interesting to note that the different Hasidic sects each have their own syllables, and each may boast that their syllables are the best. So the ‘Yam bim bom’ sect does not mingle with the ‘Ya da day’ sect, nor, heaven forbid, the ‘Ya gi di gi day’ gang! And intermarriage? Completely out of the question!

Music for Celebrations and Communal Life – Sephardi

Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) repertoire

As already mentioned, the term Sephardi literally means ‘Spanish’ in Hebrew. It denotes that significant portion of Jewish cultural identity stemming originally from Spain, in the post-1492 expulsion centuries. There was a thriving Jewish community on the Iberian Peninsula for centuries, and this included North Africa as well. Some of Judaism’s greatest Rabbis, like Moses Maimonides, and poets like Judah Halevi, lived in Spain and North Africa in the 11th and 12th centuries. After the expulsion from Spain in 1492 and Portugal in 1497, these communities were dispersed all around the Mediterranean, as well as to northern places like Amsterdam and London. They took with them their Spanish of the 15th century and continued to utilize it as a vernacular. This language, called Ladino, already mixed with Hebraic terms, and tinged with Hebraic linguistic construction, added new words from the languages of the cultures where Jews found themselves.

There is a very large Ladino repertoire, songs that were kept alive by Jewish musicians and that are still sung and played. Interestingly, much of the repertoire is comprised of songs in a secular and romantic vein, and to the best of my understanding, were kept alive by women as part of celebratory events like weddings.

North African/Arabic influences, modes, and rhythms

Regarding the musical materials themselves, there is no strict system of modes compiled for the Sephardic stream, as there is in the Ashkenazi stream. However, modes are definitely utilized, and some of them, stemming from the communities of North Africa and the Near East, like Turkey, are tinged with the Arabic musical experience.

Thus, Sephardic music is made up of songs in Ladino, plus music that integrates the modes and rhythms of Arabic and Turkish music.

In this context, it is important to differentiate Sephardi and Mizrahi cultural expressions. While both have integrated some modes and rhythms of the Arabic-Turkish-Persian systems of music, I would say that what typifies the Mizrahi stream is that it eschews harmonic expression in deference to the very strong nuances of microtonal inflections – or what we may call ‘in-between notes’. Harmony, the way we conceive of it in the West, only gets in the way of the melodic expression of Mizrahi modes.

Music for Celebrations and Communal Life – Mizrahi

In Israel, some of the songs and modes of Mizrahi music have been harmonized, so their pure form is lost. This is part of the intercultural synthesis at the heart of the Jewish Musical experience. There are examples from the Tzimmes repertoire which illustrate this whereby a song comes across as more Westernized.

In part 2, there are several more examples of Mizrahi musical expression, but for now suffice it to say that in Mizrahi communities singing and celebrating in song has been practiced as much as anywhere in the Jewish world. And the music in the Middle Eastern cultures where Jews resided over the centuries, incorporates a wide range of song forms and instrumental music for ensembles.

So, from Turkey, eastward to Uzbekistan, Jewish musicians have participated in and helped develop the music of the cultures in which they resided. To some degree, this may have been due to the proscription, in strict Moslem circles, against the occupation of musician itself, and of music making for its own sake. Interestingly, in Jewish jurisprudence, music-making was likewise seen as somewhat less than holy, because, from the theological point of view, Jewish people have been in a state of mourning since the loss of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. However, authoritative Rabbis no less illustrious than Moses Maimonides, a 12th-century giant of Jewish law, pointed out that it is not natural to keep people from celebrating with music and dance, and in fact the Rabbinic consensus is that it is a mitzvah (a good deed as commanded by God) to do so. As a klezmer myself, who has played countless weddings and other Jewish life-passage celebrations, the mitzvah I am hired to facilitate and perform is generally called – Making the Bride and Groom Happy! And the way we do this is, you guessed it, by playing lively music and getting everyone to dance a hora, a circle dance, till they drop! It’s the same for all Jews, only that the more orthodox will create separate circles for men and women.

So with this we conclude part 1 of The Many Worlds of Jewish Music. In part 2 we shall make the case for the Intercultural Synthesis at the root of the Jewish Musical experience.

The Many Worlds of Jewish Music – Part 1

Important Notice

The Many Worlds of Jewish Music

is a non-monetized presentation,

created exclusively for educational purposes.

Music Credits

Ani Ma-amin – movement V

(I Believe)

by Moshe Denburg

Vancouver Inter-Cultural Orchestra and Laudate Singers

Lars Kaario, conductor

Sheyibane Beit Hamikdash

(May the Holy Temple Be Rebuilt)

Traditional Synagogue Prayer

Performed by Moshe Denburg

Shein Vi Di Levone

(As Beautiful as the Moon)

by J. Rumshinsky and C. Tauber

Performed by Tzimmes

Kiddush

Traditional Sabbath Eve Benediction

Music by Kurt Weill

Performed by Cantor Azi Schwartz

and the RIAS Kammerchor Berlin

Havdala Song

Traditional prayer for concluding the Sabbath

Music by Debbie Friedman

Studio recording by Debbie Friedman

Hu Eloheinu

(He is Our God)

Synagogue Liturgy to the tune of

Erev Shel Shoshanim (Evening of Roses)

by Yosef Hadar

Performed by Moshe Denburg

Yome Yome

Traditional Yiddish Repertoire

Adapted and Arranged by Moshe Denburg

Performed by Tzimmes

Ahava Raba/Hava Nagila

Demonstration of Traditional mode for Synagogue and Klezmer

by Moshe Denburg

Siman Tov uMazal Tov

Traditional Celebration song

Performed by Cantor Azi Schwartz

Siman Tov uMazal Tov

Demonstration of Freylakh Rhythm

by Moshe Denburg

Cuando El Rey Nimrod

(When King Nimrod)

Traditional Ladino Repertoire

Arranged by Moshe Denburg

Performed by Tzimmes

Adon Has’lichot

(Master of Forgiveness)

Text: Hymn for the concluding service on Yom Kippur

Music: Traditional Mizrahi Repertoire

with additional music by Avishai and Itzik Eshel

Shuvi Shuvi

(Return, Return)

Texts from the Song of Songs

Music by Moshe Denburg

Performed by Tzimmes

Bukharester Bulgar

Traditional Klezmer Repertoire

Performed by the Klezmer Conservatory Band

Russian Sher

Traditional Klezmer Repertoire

YouTube credit: Maurice Le Gaulois; Paolo Driussi

Russian Sher

Traditional Klezmer Repertoire

Performed by Tzimmes

Yossel Yossel

by Samuel Steinberg and Nellie Casman

Performed by Tzimmes

Nigun Maor

(A Song of Light)

Music by Moshe Denburg

Sung by Moshe Denburg

with the Neginah Orchestra

Arranged by Yisroel Lamm

Simkha L’Artsecha

(Joy to Your Land)

Text: Liturgy of the High Holidays

Music: Traditional melody of the Modjitzer Hassidim

Performed by Tzimmes

Avre Tu Puerta Serada

Traditional Ladino Repertoire

Adapted by Moshe Denburg

Performed by Tzimmes

Shdemati – River of Light

Shdemati (My Field) by Yitzhak Shenhar

& Yedidia Admon

River of Light by Moshe Denburg

Performed by Tzimmes

Arrelumbre

(Shine)

Traditional Ladino Repertoire

Adapted, Arranged, and Performed by

Tamar Ilana and Ventanas

Mizrahi Mode in Congregational Singing

Excerpted from The Mizrahi Project

youtube.com/watch?v=ulEoW5eCNOU

Maqam Bayati

Excerpted from Maqam World

maqamworld.com/en/maqam/bayati.php

Shabhi Yerushalayim

(Praise the Lord, O Jerusalem)

Text: Psalms CXLVII, v. 12-13

Music: Avihu Medina

Arranged by Moshe Denburg

Performed by Tzimmes

Debka Hasid

Music: Traditional and Original

Adapted and Arranged by Moshe Denburg

Performed by Tzimmes

Resources on Jewish Music – https://www.tzimmes.net/jewish-music/overview