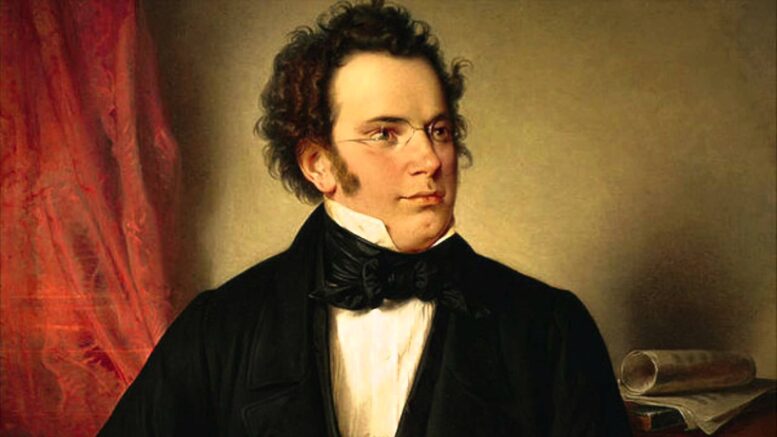

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

The Prolific Young Romantic

Franz Schubert was only 31 when he died after having been very ill for a few years due to syphilis. He was the first freelance composer without a church position nor noble patronage. Schubert was born in 1797 in Vienna, the 12th of 14 children. His mother worked as a maid before her marriage and his father was a schoolmaster, who began giving Franz violin lessons when he was 8. Franz then studied piano, organ and harmony with the organist and choirmaster of the local church and played viola in the family string quartet with 2 of his brothers and father. At 11, Franz won a choir scholarship to the Imperial Seminary, a boarding school for the common folk, where he studied with the composer Antonio Salieri. There he met his lifelong friend, Joseph von Spaun, whose family was well off, and who provided Franz with a steady supply of music manuscript paper. Franz was allowed to conduct the school orchestra several times.

When he was 15 , Franz’s mother died. The following year he left the school, moved back home, and underwent teacher training. The following year he began teaching at his father’s school, while giving private music lessons and continued taking private composition lessons with Salieri for 3 years.

Schubert’s unhappiness as a school teacher manifested in bouts of depression and throughout his life he suffered from mood swings. Fortunately, his friend, Franz von Schober, invited Schubert to live at his mother’s house. This gave him the freedom to compose as much as he wanted to. While there was no piano in the Schubert home, the Schober family did have a piano, which made a huge difference to the young Schubert. Within a year though, he moved back home, rejoining his father, and reluctantly resumed his teaching duties.

The largest land-owners of the Habsburg Empire were members of the Esterhazy family.

Schubert spent the summer of his 21st year living with the family in Slovakia, making good money as their music teacher, while still having lots of time to compose.

After that summer he began living with his friend Johann Meyerhofer. Beginning in the early 1820s Schubert was part of a group of artists and students who met regularly for social evenings called Schubertiads, during which his chamber music and songs were often performed. Schubert was only slightly taller than 5 feet and was nicknamed “little mushroom”.

In early 1820 Schubert and four of his friends were arrested by the Austrian police who were suspicious of any gatherings of youth. They were especially suspicious of potential revolutionary activities in the aftermath of the French Revolution. One of Schubert’s friends was imprisoned for over a year and then banned from Vienna. Schubert and the other three were severely reprimanded for insulting the officials.

Schubert composed innumerable sketches before he was satisfied with a composition’s completion. He was incredibly prolific, having composed more than 1,500 compositions before his death at age 31 including 15 string quartets, 9 symphonies, 21 piano sonatas, and many hundreds of other compositions. He even composed several operas and ballets! He would sometimes write four versions of a song before he was satisfied. Unfortunately, having written over 600 songs, he was only recognized as a composer of songs during his lifetime and for many years after his death.

Schubert only gave one public concert in his life, 7 months before his death. It consisted entirely of his own music, and unfortunately it received very little press coverage because of the upcoming appearance in Vienna of the legendary violin virtuoso Niccolo Paganini. The anticipation of Paganini’s appearance completely overshadowed coverage of Schubert’s concert in the press.

Schubert wrote a sonata for piano and arpeggione, an instrument somewhat similar to the cello. Mstislav Rostropovich recorded it with the English composer, Benjamin Britten, as pianist. Rostropovich’s daughters and the cellist Moshe Maisky recall their unique collaboration and friendship. When the recording was played for Rostropovich as he lay in a coma on his deathbed, tears rolled down his face.

In the last year of his life, Schubert again lived as a guest in the Schober home. He had 2 1/2 rooms to himself, which was a more comfortable living situation than he ever had before. Several weeks before his death he moved in with his brother’s family. Wanting to improve his ability at composing fugues, he had his first and what turned out to be his only lesson with Simon Sechter two weeks before he died.

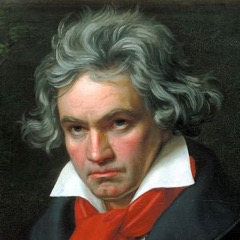

Schubert was a great admirer of Beethoven. Contrary to the story that some of Schubert’s music was shown to Beethoven when the latter was on his deathbed and that Beethoven said some very nice things about Schubert’s music, Schubert told his life-long friend, Joseph von Spaun, that he had never met, nor spoken to Beethoven. He did visit the composer a week before Beethoven’s death, and he was one of the torchbearers at Beethoven’s funeral.

The following year, when Schubert was lying on his deathbed he requested that a string quartet come and play for him Beethoven’s 14th Quartet. He died from syphilis when he was just 31. He may have also had typhoid fever. He wanted to be buried near Beethoven’s grave and he was.

Schubert set several texts to music that are based on the Old Testament including Psalms 13, 23 and 92. In fact his very first song written at age 14 is Hagar’s Lament. It’s a biblical story, in which Abraham’s wife, Sarah, could not bear children, so she allowed Abraham to conceive a child with the slave Hagar, who gave birth to Ishmael.

Near the end of his life, Schubert composed Miriam’s Victory based on a story from the Bible in which God parted the Red Sea to allow the Israelites to return to their homeland. Miriam, the sister of Moses and Aaron, celebrated when God closed up the sea, trapping and drowning Pharaoh and his army. Schubert composed the scene for soprano solo, chorus and piano. After Schubert’s death, several composers orchestrated it.

In 1821 the Emperor had ennobled nine Jews, and he agreed that a new synagogue be built in Vienna, the first of its kind since 1671. Its cantor, Salomon Sulzer, felt that music by non-Jewish composers might be heard at the Friday night and Saturday services, and invited Schubert to compose for the new synagogue; thus Schubert’s setting of Psalm 92 Tov lehodos for the Sabbath, written just 4 months before his death. Schubert could have set it in German but chose instead to set it in Hebrew for a group of soloists alternating with a chorus and included a baritone solo for Sulzer. There is nothing like this in Schubert’s other choral music, and it is based on the tradition of the cantor singing melodies with a boy soprano and a bass on either side of him, who accompanied his melodies. It is clear that Schubert consulted Sulzer on matters of Hebrew accentuation and meaning. Schubert’s musical genius enabled him to be a link between different cultures and faiths.

Referring to the beautiful lyricism of Schubert’s melodies, my teacher, Dr. Anthony LaMagra said: “Everything he wrote was a song.”

Schubert had great difficulty earning income. Publishers were very hesitant to publish his music. In fact, he never got to hear much of it performed, and for decades after his death much of his music remained unpublished. What was published during his lifetime were mostly songs, waltzes, and marches because he wasn’t thought of as a serious composer, but rather as just a mere song composer. He actually composed over 600 songs. So his music was only known through his friends, followers, and high society, where people could play these compositions in their homes.

In the cycle of 24 songs entitled Die Wintereise, The Winter Journey, Schubert created incomparable scenes of despair, heartbreak, violence, and numbness, in a landscape of snow, ice, and bitter wind.

The great soprano, Lotte Lehmann, wrote about Die Wintereise: “The last 12 songs in the cycle show the gloom gathering about him, the infinite sadness which had taken hold of Schubert at the time he composed them.” In Schubert’s own words: “When I wished to sing of love, it turned to sorrow. And when I wished to sing of sorrow, it was transformed for me into love.”

When Schubert completed Die Wintereise, he played and sang all of its 24 songs for his close friends. Their reaction was not enthusiastic. To that, he said “I like these songs more than all the rest and you will come to like them as well.”

What’s tragic about Schubert is that he had great difficulty making a living. By the time people slowly began accepting him as a serious composer, he had contracted syphilis, and his final few years were filled with suffering from various physical ailments. At age 27 he wrote to his friend Leopold Kupelwieser: “I feel myself the most unfortunate, the most miserable being in the world. My peace is gone, my heart is heavy, I find it never, never more… Each night when I go to sleep I hope never again to wake, and each morning merely reminds me of the misery of yesterday. My affairs are going badly, so we never have any money. Now I close, so as not to use too much paper and I and kiss you a thousand times if you would write to me about your own enthusiasms and your life as well, nothing would more greatly please Your faithful friend Franz Schubert”.

As his biographer, Maurice Brown wrote: “It is impossible to imagine the contentment and high spirits of the Octet born from this despairing mind.” The Octet and the letter were written in the same month! Schubert’s Octet is his longest chamber composition, lasting more than an hour! It was written for 2 violins, viola, cello, bass, French horn, bassoon and clarinet.

One of the greatest songs ever written is An die Musik, To Music. It is Schubert’s setting of his friend, Franz von Schober’s poem, An die Musik. It’s an expression of gratitude to music! Lotte Lehmann was a great, legendary soprano, who sang so expressively, the Viennese called her “the singing soul”. She sang the world premieres of operas by Erich Korngold and Richard Strauss, and sang several times with Toscanini in New York and Salzburg. She wrote about An die Musik: “I always think of this song as a prayer, an expression of deep gratitude to music felt deeply at a time when there is so much suffering elsewhere.”

A year before he died Schubert did some local traveling and mountain climbing with his friend Johann Jenger. They were guests at the homes of various friends. In a letter to one of his hosts, Schubert wrote: “I shall never forget the kindly shelter, where I spent the happiest days I have had for a long time.”

Decades after his death Schubert’s music was eventually published and several composers and conductors have orchestrated his music for piano, songs, and chamber music.